Introduction to Quantum Mechanics

This page is print-friendly. Simply press Ctrl + P (or Command + P if you use a Mac) to print the page and download it as a PDF.

Table of contents

Note: it is highly recommended to navigate by clicking links in the table of contents! It means you can use the back button in your browser to go back to any section you were reading, so you can jump back and forth between sections!

- Why quantum theory?

- Getting started with quantum mechanics

- Mathematical foundations

- Solutions as eigenstates

- Quantum operators

- Solving quantum systems

- The mathematics behind quantum mechanics

- The fundamental postulates of quantum mechanics

- The classical limit of quantum mechanics

- A brief peek at more advanced quantum mechanics

- Further reading

This a mini-book on quantum mechanics at a beginner's level, with topics covered including wavefunctions, various solutions of the time-dependent and independent Schrödinger equation, the uncertainty principle, and expectation values.

Why quantum theory?

Niels Bohr doing quantum mechanics - source

Quantum theory is our best understanding of how the universe works at its most fundamental level. It is fundamentally paradoxical to human experience, but it is the bedrock of almost all of modern physics and its predictive power has made technological innovations possible. In addition, it is also a very scientifically and philosophically interesting theory to learn. This article forms the basis of an introduction to quantum mechanics.

Getting started with quantum mechanics

Our understanding of classical physics has served us well for centuries and still makes very accurate predictions about the world. But since the 20th century, we have found that the classical mechanics is actually only part of a much broader theory - quantum mechanics - that applies in many areas that classical theory fails. Quantum theory can explain the same phenomena that classical physics can, but it explains so much more that classical physics can't. It is truly a pillar - and wonder - of modern physics. In fact, it is the most accurate theory of physics ever created, especially with its subdiscipline of quantum field theory - and specifically, quantum electodynamics - that predicts quantities so precisely that they have been confirmed to ten parts in a billion.

But quantum theory can be difficult to comprehend, in part because it is founded on very different principles as compared to classical physics:

- The Universe is fundamentally described by probability distributions, as opposed to objects with exact positions and trajectories

- Physical quantities can only take on particular values and exact knowledge about them is often impossible

- Properties of quantum particles include many that don't exist for classical particles, such as the ability to pass through a solid barrier and having a nonzero energy even when stationary in a region of zero potential energy

We don't know why we observe the world to behave in this way, and the interpretation of quantum mechanics is a separate philosophical question. Rather, we will simply consider the theory as a model that makes accurate predictions about the world without delving into why.

In the first few sections, we'll introduce quantum mechanics without explaining why it works. Consider this as simply a preview of the essential features of quantum mechanics. In the sections after, we'll actually explain why quantum theory works, and derive many of the relations we take for granted in applying quantum mechanics.

Mathematical foundations

What follows is a relatively brief mathematical overview of only the fundamentals required for starting quantum physics. However, it would certainly be helpful to have a background in multivariable calculus, differential equations, and some linear algebra (vectors, matrices, and eigenvalues). Don't worry if these are alien topics! There are expanded guides to each in the calculus series. In addition, while not required, the introductory classical dynamics series can be very helpful as well.

Eigenvalues and eigenfunctions

To start with understanding quantum theory, we must first start with a concept that may be familiar to those who have studied linear algebra, although knowledge of linear algebra is not required. Consider the function $y(x) = e^{kx}$. If we take its derivative, we find that:

$$ \dfrac{dy}{dx} = ke^{kx} $$

Which we notice, can also be written as:

$$ \frac{dy}{dx} = ky $$

Notice that the derivative of $y(x)$ is just $y(x)$ multiplied by $k$. We call $y(x)$ an eigenfunction, because when we apply the derivative, it just becomes multiplied by a constant, and we call the constant here, $k$, an eigenvalue. The exponential function is not the only function that can be an eigenfunction, however. Consider the cosine function $y(x) = \cos kx$. Taking its second derivative results in:

$$ \frac{d^2 y}{dx^2} = -k^2 \cos kx = -k^2 y $$

So cosine is also an eigenfunction, except its eigenvalue is $-k^2$ rather than $k$. We can show something very similar with sine - which makes sense because a sine curve is just a shifted cosine curve.

Complex numbers

In quantum mechanics, we find that real numbers are not enough to fully describe the physics we observe. Rather, we need to use an expanded number system, that being the complex numbers.

A complex number can be thought of as a pair of two real numbers. First, we define the imaginary unit $i = \sqrt{-1}$. To start, this seems absurd. We know that no real number can have this property. But the fact that complex numbers do have this properties gives rise to many useful mathematical properties. For instance, it allows for a class of solutions to polynomial equations that can't be expressed in terms of real numbers.

We often write a complex number in the form $z = \alpha + \beta i$, where $\alpha$ is called the real part and $\beta$ is called the imaginary part. For a complex number $z$, we can also define a conjugate given by $\bar z = \alpha - \beta i$ (some texts use $z^*$ as an alternative notation). Uniquely, $z \bar z = (\alpha + \beta i)(\alpha - \beta i) = \alpha^2 + \beta^2$.

Complex numbers also have another essential property. If we define the exponential function $f(x) = e^x$ in a way that allows for complex arguments, i.e. $f(z) = e^{z} = e^{\alpha + \beta i}$, we find that $e^{i\phi} = \cos \phi + i \sin \phi$. This is called Euler's formula and means we can use complex exponentials to write complex numbers in the form $z = re^{i\phi}$ where $r = \sqrt{\alpha^2 + \beta^2}$ and $\phi = \tan^{-1} \beta/\alpha$, converting to trigonometric functions whenever more convenient and vice-versa.

But why do we use - or care - about complex exponentials? Mathematically speaking, complex exponentials satisfy all the properties of exponential functions, such as $e^{iA} e^{iB} = e^{i(A + B)}$ and $e^{iA} e^{-iB} = e^{A-B}$. This greatly simplifies calculations.

For a more in-depth review, it may be helpful to see the refresher on logarithmic and exponential functions here.

In addition, Euler's formula results in several identities that are also very helpful in calculations. From $e^{i\phi} = \cos \phi + i\sin \phi$ we can in turn find that $e^{i\phi} + e^{-i\phi} = 2\cos \phi$ and $e^{i\phi} - e^{-i\phi} = 2i \sin \phi$. We will use these extensively later on.

The study of calculus that applies to complex numbers is called complex analysis. For most of quantum mechanics, we won't need to do full complex analysis, and can treat $i$ as simply a constant. There are, however, some advanced branches of quantum mechanics that do need complex analysis.

The wave equation

In classical physics, the laws of physics are described using differential equations. Differential equations are a very, very broad topic, and if unfamiliar, feel free to read the dedicated article on differential equations. Their usefulness comes from the fact that differential equations permit descriptions of large classes of different physical scenarios. Consider, for instance, the wave equation:

$$ \frac{\partial^2 y}{\partial t^2} = v^2 \frac{\partial^2 y}{\partial x^2} $$

This partial differential equation models everything from water ripples in a pond to the vibrations of a drum and even to light - which is an electromagnetic wave. The last one, however, is particularly important for quantum mechanics, because light is fundamentally quantum in nature, and the study of light is a crucial part of quantum mechanics.

To solve the wave equation, we may use the separation of variables. That is to say, we assume that the solution $y(x, t)$ is a product of two functions $f(x)$ and $g(t)$, such that:

$$ y(x, t) = f(x) g(t) $$

This means that we can take the second partial derivatives of $y(x, t)$ as follows.

$$ \begin{align*} \dfrac{\partial^2 y}{\partial x^2} &= \dfrac{\partial^2}{\partial x^2} \left(f(x) g(t)\right) = g(t) \dfrac{\partial^2}{\partial x^2} f(x) \\ &= g(t) \dfrac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x^2} \\ \dfrac{\partial^2 y}{\partial t^2} &= \dfrac{\partial^2}{\partial t^2} \left(f(x) g(t)\right) = f(x) \dfrac{\partial^2}{\partial t^2} g(t) \\ &= f(x) \dfrac{\partial^2 g}{\partial t^2} \\ \end{align*} $$

Note that we are able to factor out $g(t)$ when taking the second derivative of $y(x, t)$ with respect to $x$ because $g(t)$ doesn't depend on $x$, and therefore we can treat it as a constant. The same principle applies when taking the second derivative of $y(x, t)$ with respect to $t$; as $f(x)$ doesn't depend on $t$, we can also treat it as a constant and factor it out of the second derivative.

If we substitute these expressions for the second derivatives back into the wave equation $\partial_{t}{}^2 y = v^2 \partial_{x}{}^2 y$ we have:

$$ f(x) \dfrac{\partial^2 g}{\partial t^2} = v^2 g(t) \dfrac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x^2} $$

Note on notation: Here $\partial_{t}{}^2 y$ is a shorthand for $\dfrac{\partial^2 y}{\partial t^2}$ and $\partial_{x}{}^2 y$ is a shorthand for $\dfrac{\partial^2 y}{\partial x^2}$.

From our substituted wave equation, we can now perform some algebraic manipulations by dividing both sides by $f(x) g(t)$ and then multiplying both sides by $\dfrac{1}{v^2}$, as shown:

$$ \begin{align*} \dfrac{1}{f(x) g(t)} f(x) \dfrac{\partial^2 g}{\partial t^2} &= \dfrac{1}{f(x) g(t)}v^2 g(t) \dfrac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x^2} \Rightarrow \\ \dfrac{1}{g(t)} \dfrac{\partial^2 g}{\partial t^2} &= v^2 \dfrac{1}{f(x)}\dfrac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x^2} \\ \dfrac{1}{v^2 g(t)} \dfrac{\partial^2 g}{\partial t^2} &= \dfrac{1}{f(x)}\dfrac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x^2} \end{align*} $$

However, if two expressions involving different partial derivatives are equal each other, then they must both be equal to a constant. This is called the separation constant, which we can set to a generic constant that can be positive or negative in sign (as the sign doesn't change the fact that it is constant), multiplied by any other constant, or raised to any power, as none of these operations change the fact that the end result is a constant. If we let that constant be $-k^2$ (we can choose any other constant or sign but this particular choice makes calculations easier later), we have:

$$ \dfrac{1}{v^2 g(t)} \dfrac{\partial^2 g}{\partial t^2} = \dfrac{1}{f(x)}\dfrac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x^2} = -k^2 $$

Which means we have separated the wave equation into two differential equations, one only involving $f(x)$, and one only involving $g(t)$:

$$ \dfrac{1}{v^2 g(t)} \dfrac{\partial^2 g}{\partial t^2} = -k^2 \\ \dfrac{1}{f(x)}\dfrac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x^2} = -k^2 $$

This is the method of separation of variables, which is covered in the differential equations guide as well as the solving separable PDEs guide. The idea is to reduce a partial differential equation into several ordinary differential equations that are easier to solve.

At this point we should note that since $g(t)$ is purely a function of $t$ and $f(x)$ is purely a function of $x$, neither are multivariable functions and thus the partial derivatives reduce to ordinary derivatives:

$$ \dfrac{1}{v^2 g(t)} \dfrac{d^2 g}{d t^2} = -k^2 \\ \dfrac{1}{f(x)}\dfrac{d^2 f}{d x^2} = -k^2 $$

We can algebraically rearrange terms in both equations to get them into a slightly nicer and cleaner form:

$$ \begin{align*} \dfrac{d^2 g}{d t^2} &= -k^2 v^2 g(t) \\ \dfrac{d^2 f}{d x^2} &= -k^2 f(x) \end{align*} $$

If we define another constant named $\omega$ which is defined as $\omega \equiv kv$ ($\equiv$ is the symbol for "defined as") we can rewrite even more nicely as:

$$ \begin{align*} \dfrac{d^2 g}{d t^2} &= -\omega^2 g \\ \dfrac{d^2 f}{d x^2} &= -k^2 f \end{align*} $$

Solving these ordinary differential equations involves finding functions $g(t)$ and $f(x)$ whose second derivatives are equal to themselves, multiplied by a constant. We can use the ansatz's (ansatz is a fancy German-derived word for "educated guess") of complex exponential functions as the solutions, and then check that this does indeed work:

$$ \begin{align*} g(t) &= e^{-i\omega t} \rightarrow \dfrac{d^2 g}{dt^2} = -\omega^2 e^{-i\omega t} = -\omega^2 g(t) \\ f(x) &= e^{-ik t} \rightarrow \dfrac{d^2 f}{dt^2} = -k^2 e^{-ik t} = -k^2 f(x) \\ \end{align*} $$

However, we find that $g(t) = e^{i\omega t}$ and $f(x) = e^{ikx}$ also works:

$$ \begin{align*} g(t) &= e^{i\omega t} \rightarrow \dfrac{d^2 g}{dt^2} = -\omega^2 e^{i\omega t} = -\omega^2 g(t) \\ f(x) &= e^{ik t} \rightarrow \dfrac{d^2 f}{dt^2} = -k^2 e^{ik t} = -k^2 f(x) \\ \end{align*} $$

So we write the general solution as a linear combination (i.e. sum with constant coefficients) of the two respective solutions for each:

$$ g(t) = C_1 e^{i\omega t} + C_2 e^{-i\omega t} \\ f(x) = C_3 e^{ik x} + C_4 e^{-ik x} \\ $$

Now recalling that we set $y(x, t) = f(x) g(t)$ we can substitute our solutions to get the general solution for the 1D wave equation:

$$ y(x, t) = \left(C_1 e^{i\omega t} + C_2 e^{-i\omega t}\right)\left(C_3 e^{ik x} + C_4 e^{-ik x}\right) $$

Note for the mathematical reader: Technically speaking, this is not the most general solution, as any linear combination of this solution is a solution, given that the wave equation is a linear partial differential equation (PDE). Furthermore, given that one may always add a function to a solution to a PDE that gets differentiated away (as taking a partial derivative of a function with respect to a variable that the function doesn't depend on gives zero), the most general solution is actually $y(x, t) = u(x - vt) + w(x + vt)$ for any two twice-differentiable functions $u, w$.

Expanding the solution we obtained out, we have:

$$ \begin{align*} y(x, t) &= C_1 C_3 e^{i\omega t} e^{ikx} + C_1 C_4 e^{i\omega t} e^{-ikx} + C_2 C_3 e^{-i\omega t} e^{ikx} + C_2 C_4 e^{-i\omega t} e^{-ikx} \\ &= (C_2 C_3 e^{ikx - i\omega t} + C_1 C_4 e^{-ikx + i\omega t}) + (C_1 C_3 e^{ikx + i\omega t} + C_2 C_4 e^{-ikx -i\omega t}) \\ & = (C_2 C_3 e^{i(kx - \omega t)} + C_1 C_4 e^{-i(kx - \omega t)}) + (C_1 C_3 e^{i(kx + \omega t)} + C_2 C_4 e^{-i(kx + \omega t)}) \end{align*} $$

We note that this general solution is actually a sum of two wave solutions, one that travels along the $+x$ axis as time progresses, and one that travels along the $-x$ axis as time progresses. Thus we may write $y(x, t)$ as a sum of the rightward-traveling solution $y_1(x, t)$ and the leftward-traveling solution $y_2(x, t)$:

$$ \begin{align*} y(x, t) &= y_1(x, t) + y_2(x, t) \\ y_1(x, t) &= C_2 C_3 e^{i(kx - \omega t)} + C_1 C_4 e^{-i(kx - \omega t)} \\ y_2(x, t) &= C_1 C_3 e^{i(kx + \omega t)} + C_2 C_4 e^{-i(kx + \omega t)} \end{align*} $$

We can write this in a neater form by defining $A \equiv C_2 C_3, B \equiv C_1C_4, C \equiv C_1 C_3, D \equiv C_2 C_4$ and therefore we may write:

$$ \begin{align*} y(x, t) &= y_1(x, t) + y_2(x, t) \\ y_1(x, t) &= Ae^{i(kx - \omega t)} + B e^{-i(kx - \omega t)} \\ y_2(x, t) &= C e^{i(kx + \omega t)} + D e^{-i(kx + \omega t)} \end{align*} $$

We call these solutions wave solutions (unsurprisingly) and all wave solutions have an associated wavelength $\lambda$ and frequency $f$ as well as amplitude(s) $A, B, C, D$. From these we can derived more quantities that explicitly appear in the solution: $k = 2\pi/\lambda$ is known as the wavevector and $\omega = 2\pi f$ is the angular frequency related through $\omega = k v$ (as we saw earlier in the solving process). Here, $v$ is the speed the wave propagates forward.

A pecular feature is that $y(x, t)$ is actually a standing wave, meaning that it does actually move, because $y_1, y_2$ move in opposite directions to each other, and thus their effects cancel out when they are added together.

Now, let us turn our attention to a wave equation that can be considered the classical entryway into quantum theory. The electromagnetic (EM) wave equation is a special case of the wave equation given by:

$$ \dfrac{\partial^2 E}{\partial t^2} = c^2 \dfrac{\partial^2 E}{\partial x^2} $$

where $c$ is the speed of light in vacuum and $E(x, t)$ is the magnitude of the electric field, whose oscillations produce electromagnetic waves, that is, light. The solutions to the EM wave equation are also a special case of the general solution we have just derived for the wave equation:

$$ \begin{align*} E(x, t) &= E_1(x, t) + E_2(x, t) \\ E_1(x, t) &= Ae^{i(kx - \omega t)} + B e^{-i(kx - \omega t)} \\ E_2(x, t) &= C e^{i(kx + \omega t)} + D e^{-i(kx + \omega t)} \end{align*} $$

Where $A, B, C, D$ are amplitudes derived from the boundary conditions of a specific problem. The solution characterizes all forms of light and radiation propagations, including all the light we see. The solution is uniquely characterized by two fundamental quantities, the speed of light $c$ and the wavelength of light $\lambda$, as well as its amplitudes (the electric field strength, in physical terms). All other quantities appearing in the solution can be derived from these two:

| Quantity | Expression in terms of $\lambda$ and $c$ |

|---|---|

| $k$ | $\dfrac{2\pi}{\lambda}$ |

| $f$ | $\dfrac{c}{\lambda}$ |

| $\omega$ | $k c = 2\pi f = \dfrac{2\pi c}{\lambda}$ |

Wave solutions have some particular characteristics: they oscillate in time in predictable ways (which is why we can ascribe a frequency to them), and complete each spatial oscillation over a predictable distance (which is why we can ascribe a wavelength). Despite not being waves, quantum particles behave in ways strikingly similar to solutions of the wave equation, and also have a frequency and wavelength as well as derived quantities such as $k$ and $\omega$. In addition, characterics of waves and how they interact with objects have a big part to play in quantum phenomena, as we will soon see.

The Schrödinger equation

In the quantum world, particles no longer follow the laws of classical physics. Instead, they follow the Schrödinger wave equation, a famous partial differential equation given by:

$$ i\hbar \frac{\partial}{\partial t} \Psi(x, t) = \left(-\frac{\hbar^2}{2m} \frac{\partial^2}{\partial x^2} + V(x, t)\right) \Psi(x, t) $$

This is the 1D Schrödinger equation, but we will look at the full 3D Schrödinger equation later.

Here, $\hbar$ is the reduced Planck constant, $m$ is the particle's mass, $V(x, t)$ is the particle's potential energy (which is often referred to simply as "the potential"), and the function to be solved for is $\Psi(x, t)$.

The solutions to the Schrödinger equation $\Psi(x, t)$ for given initial and boundary conditions are called wavefunctions. The Schrödinger equation tells us that when undisturbed, quantum particles are waves spread out in space, instead of possessing definite positions. We call these waves matter waves. A quantum particle (or system) can be analyzed by finding the particular solution of the Schrödinger equation for that particle (or system), although the actual solving process is rather tedious and more of a mathematical exercise than physics. Using separation of variables is a common method to solve the Schrödinger equation, and we will work through several examples. However, lots of solutions are very well-known and just looking them up in a textbook, reference book, or online is far faster than actually solving the equation.

As is suggestive of the name, wavefunctions describe the matter wave associated with a particular quantum particle (or system of quantum particles). Just like classical waves, all quantum particles have a wavelength $\lambda$ which is related to the momentum by $\lambda = \dfrac{h}{p}$ and the energy by $\lambda = \dfrac{hc}{E}$. Here, $h = \pu{6.62607E-34 J\cdot s}$ is the Planck constant, a fundamental constant of nature, alongside the reduced Planck constant $\hbar \equiv \dfrac{h}{2\pi} = \pu{1.05457E-34 J\cdot s}$.

The equations $\lambda = \dfrac{h}{p}$ and the energy $\lambda = \dfrac{hc}{E}$ can be rewritten as $p = \hbar k$ (the de Broglie relation) and $E = \hbar \omega$ (the Planck-Einstein relation).

As a bizarre consequence of the Schrödinger equation, wavefunctions - that is, the matter waves - are complex-valued. That is to say, matter waves are not physical quantities that are observable in the real world. Furthermore, matter waves are not simply one wave, but actually contain all possible states that a quantum particle can be in, where each state is a unique wave solution to the Schrödinger equation. At a given moment, a quantum particle's actual state can be any of the states contained in the wavefunction, but which one is impossible to predict in advance.

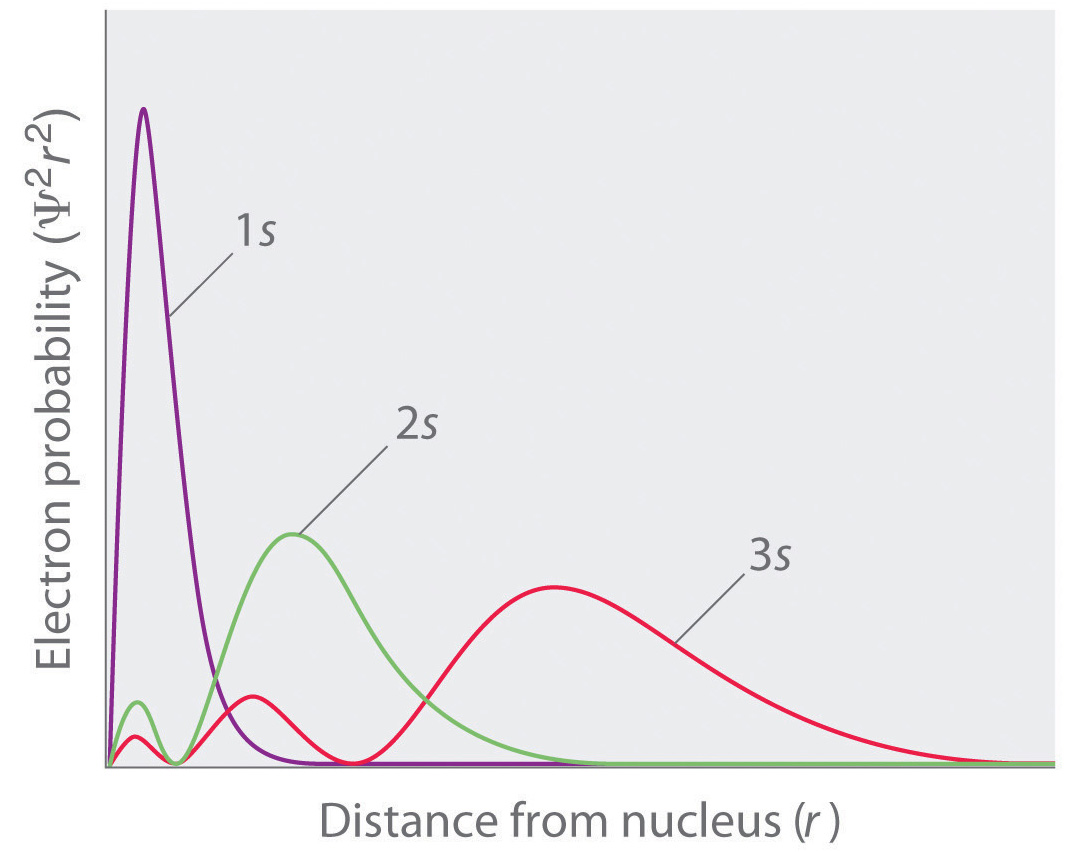

Thus, rather than physical individual waves in space, wavefunctions are more of a mathematical description of many possible quantum waves of a particle that is non-localized and cannot be predicted exactly. For instance, an electron can be in its ground state (lowest-energy state). But it can also be in a number of other excited states (energetic states). Within each state, the particle has specific energies and momenta and has different probabilities to be located at a particular point in space. In fact, squaring the wavefunction and taking its absolute value, which we write as $\rho(x) = |\Psi|^2$, gives the probability density, indicating how likely it is to find a quantum particle at a specific point $x$ in space - although theoretically the particle can be almost anywhere. For instance, the following plot showcases the probability density for three wavefunctions:

Source: Khan Academy

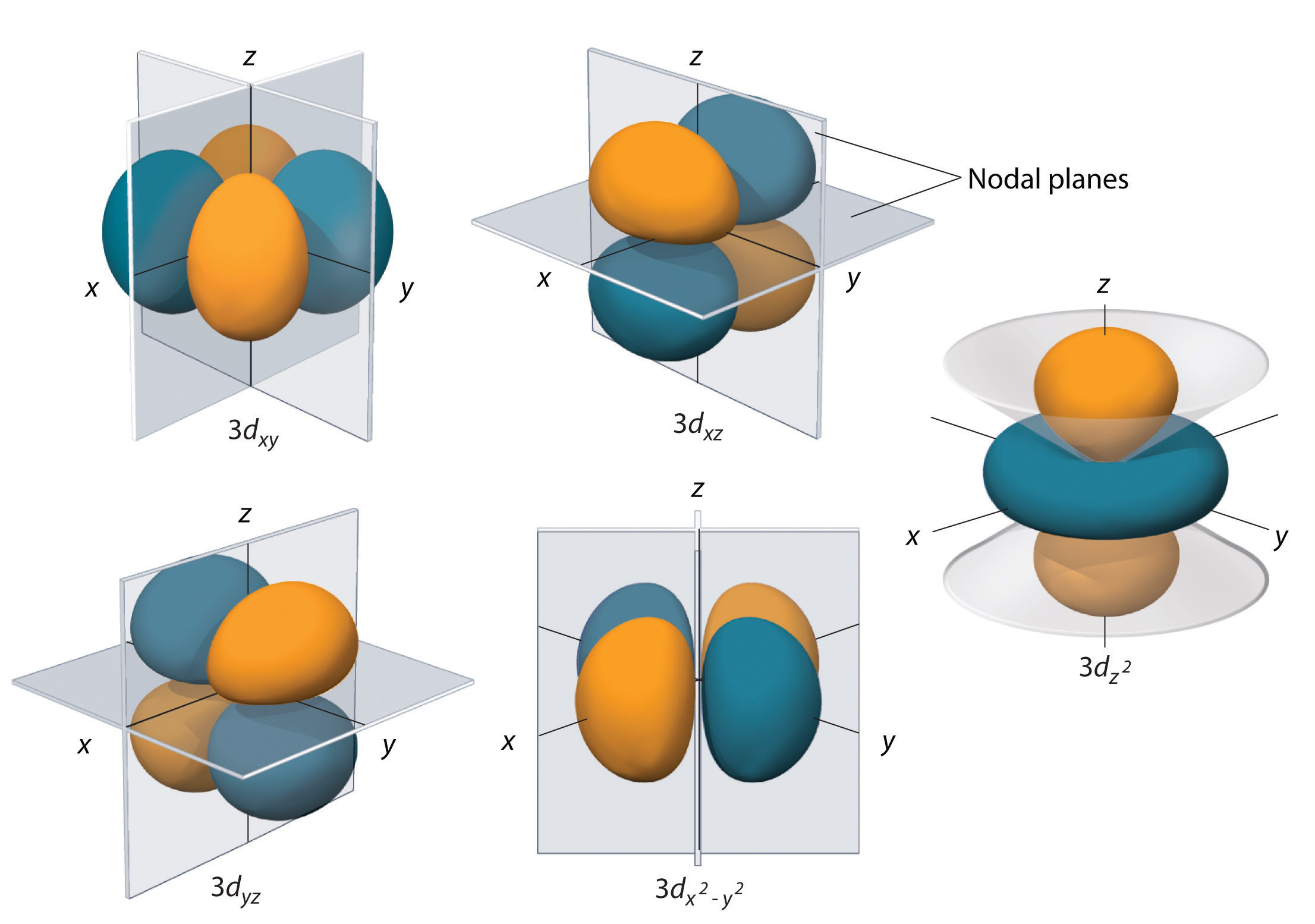

When we consider quantum problems in 3 dimensions, the associated probability density takes the form $\rho(x, y, z) = |\Psi(x, y, z)|^2$. 3D slices of the probability density for several solutions of the Schrödinger equation are shown below:

Source: LibreTexts

To re-emphasize, since quantum particles are described as complex-valued matter waves, they aren't truly point particles, but spread throughout space - hence wave equation, because these solutions carry a wavelike nature. Since these solutions display cyclical (symmetric in space) and oscillatory (repeating in time) behavior, meaning that just like classical waves, we describe them in terms of wave quantities like the wavelength $\lambda$, angular frequency $\omega$, wave propagation speed $v$, and wavevector $k$. However, when we measure a quantum particle, we find that it then behaves particle-like and occupies a particular position. The likelihood of a particle being at a particular position can be calculated from the probability density $\rho = |\Psi|^2$, and we can find which positions the particle is more (or less) likely to be located. But the precise position cannot be predicted in advance.

Definition: A quantum state $\psi(x)$ is a solution to the Schrödinger equation for a given time $t$ whose physical interpretation is the matter wave of a quantum particle (or system). Taking the squared amplitude $|\psi(x)|^2$ of the quantum state gives a unique probability distribution function describing a quantum particle (or system).

Addenum: the time-independent Schrödinger equation

It is often convenient to write out a wavefunction in terms of separate time-dependent and time-independent components. We denote the full wavefunction as $\Psi(x, t)$, and the time-independent part as $\psi(x)$, where $\Psi(x, t) = \psi(x) e^{-i E/\hbar}$ for some value of the energy $E$.

This is not simply a matter of convention. The underlying reason is that by the separation of variables technique, the Schrödinger equation can be rewritten as two differential equations in the form:

$$ \begin{align*} i\hbar \dfrac{d}{d t} \phi(t) &= E \phi(t) \\ -\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m} \dfrac{\partial^2 \psi}{\partial x^2} + V(x) \psi &= E \psi(x) \end{align*} $$

Where we refer to the bottom differential equation as the time-independent Schrödinger equation, and $\Psi(x, t) = \psi(x) \phi(t)$. Thus we say that $\psi(x)$ is a solution of the time-independent Schrödinger equation and represents the time-independent component of the wavefunction.

When applying the Schrödinger equation, it is convention (though not a rule) that a lowercase $\psi$ for $\psi(x)$ is used for the spatial component of the wavefunction that is the solution to the time-independent Schrödinger equation, and an uppercase $\Psi$ for $\Psi(x, t) = \psi(x) \phi(t)$ is used for the complete wavefunction in both time and space. This also means that $\psi(x) = \Psi(x, 0)$.

Solutions as eigenstates

The solutions to the Schrödinger equation have an important characteristic: they are linear in nature. This means that we can write the general solution in terms of a superposition of solutions, each of which is a possible state for a quantum particle (or particles) - see the differential equation series for why this works. Taking $\varphi_1, \varphi_2, \varphi_3, \dots$ to be the individual solutions with energies $E_1, E_2, E_3, \dots$, the general time-independent solution would be given by:

$$ \begin{align*} \psi(x) &= \sum_n C_n \varphi_n(x) \\ &= C_1 \varphi_1(x) + C_2 \varphi_2(x) + \dots + C_n \varphi_n(x) \end{align*} $$

And therefore the general (time-dependent) wavefunction $\Psi(x, t)$ would be given by:

$$ \begin{align*} \Psi(x, t) &= \sum_n C_n \varphi_n(x) e^{-iE_n t/\hbar} \\ &= C_1 \varphi_1(x)e^{-iE_1t/\hbar} + C_2 \varphi_2(x)e^{-iE_2t/\hbar} + \dots + C_n \varphi_n(x) e^{-iE_nt/\hbar} \end{align*} $$

Each individual solution $\varphi_n(x)$ is called an eigenstate, a possible state that a quantum particle can take. Eigenstate is just another word for eigenfunction, which we've already seen. This is because we note that each eigenstate individually satisfies the Schrödinger equation, which can be recast into the form of an eigenvalue equation:

$$ \left(-\frac{\hbar^2}{2m} \frac{\partial^2}{\partial x^2} + V(x, t)\right) \varphi_n(x) = E_n \varphi_n(x) $$

Note for the advanced reader: This is because mathematically speaking, the separation of variables results in a separation constant $E_n$ which results in an eigenvalue problem. We'll later see that $E_n$ acquires a physical interpretation as the energy.

As a demonstration of this principle, the solution to the Schrödinger equation for a particle confined in a region $0 < x < L$ is a series of eigenstates given by:

$$ \varphi_n(x) = \sqrt{\dfrac{2}{L}} \sin \dfrac{n \pi x}{L},\quad E_n = \dfrac{n^2 \hbar^2 \pi^2}{2mL^2} $$

$n$ is often called the principal quantum number, it is a good idea to keep this in mind.

Below is a plot of several of these eigenstates:

Source: ResearchGate

The general wavefunction of the particle would be given by the superposition:

$$ \Psi(x, t) = \varphi_1 + \varphi_2 + \dots = \small \sqrt{\dfrac{2}{L}} \normalsize \sum_n C_n \sin \dfrac{n \pi x}{L} e^{-iE_nt / \hbar} $$

Since the general wavefunction $\Psi(x, t)$ is a superposition of eigenstates, each eigenstate represents one state - and thus probability distribution - that a quantum particle can be in. A particle may be more or less likely to take a particular state. Typically, eigenstates are associated with energy, so a particle could have a number of different possible states, from a lowest-energy state to a highest-energy state and everything in between.

However, the actual state the particle takes cannot be predicted (as with many things in quantum mechanics). Only the probabilities of a quantum particle being in a particular state are predictable. As an oversimplified example, while an electron could theoretically be in an eigenstate where it has the same amount of energy as a star, the probability of that state is very, very low. Instead, we typically observe electrons with more "normal" energies, as electrons have a much higher probability of being in lower-energy eigenstates.

To quantify this statement in mathematical terms, the coefficients $C_n$ for each eigenstate are directly related to the probability of each eigenstate. In fact, the probability of each eigenstate is given by $P_n = |C_n|^2$. And we may calculate $C_n$ for a particular eigenstate $\varphi_n$ given the initial condition $\Psi(x, 0)$ with:

$$ C_n = \int_{-\infty}^\infty \bar \varphi_n(x) \Psi(x, 0)\, dx $$

The coefficients $C_n$ are referred to by different names; we may call them probability coefficients, probability amplitudes, or simply coefficients. Whichever name is used, it represents the same thing, where $P_n = |C_n|^2$ is the probability of measuring a given eigenstate.

Quantum operators

We have seen that we can solve for wavefunctions, which are the probability distributions of a quantum particle in space, by solving the Schrödinger equation. But we also want to calculate other physically-relevant quantities. How do we do so? Quantum theory uses the concept of operators to describe physical quantities. An operator is something that is applied to a function to get another function. A table of the most important operators is shown below:

| Name | Mathematical form |

|---|---|

| Position operator | $\hat X = x$ (multiplication by x) |

| Momentum operator | $\hat p = -i\hbar \dfrac{\partial}{\partial x}$ (1D), $\hat p = -i\hbar \nabla$ (general) |

| Angular momentum operator | General $\hat L = \mathbf{r} \times \hat p = \mathbf{r} \times -i\hbar\nabla$, z-component $\hat L_z = -i\hbar \dfrac{\partial}{\partial \phi}$ where $\phi$ is the azimuthal angle $\phi$ in spherical coordinates |

| Kinetic energy operator | $K = -\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m} \nabla^2$ |

| Potential (energy) operator | $\hat V = V$ (multiplication by the potential $V(x)$) |

| Total energy operator (time-independent) | $\hat H$ often called the Hamiltonian, the precise formulation may vary but the most common non-relativistic one is $\hat H = -\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m} \nabla^2 + \hat V$ |

| Total energy operator (time-dependent) | $\hat E = -i\hbar \dfrac{\partial}{\partial t}$ |

Note that $\hat H$, the energy operator, is named so due to its correspondence with the Hamiltonian in classical mechanics

There is a very important physical interpretation of a quantum operator: the eigenvalues of each eigenstate of a given quantum operator acting on a state gives the specific values of measurable values. For instance, the energy of one particular state is the eigenvalue of the Hamiltonian operator, and the momentum of one particular state is the eigenvalue of the momentum operator, and so forth.

To find the eigenstates and eigenvalues of physical properties of a quantum particle, we apply each operator to the wavefunction, which results in an eigenvalue equation that we can solve for the eigenvalues. For example, for finding the momentum eigenstates, we can apply $\hat p$ the momentum operator:

$$ \hat p \varphi = -i\hbar \dfrac{\partial}{\partial x} \varphi(x) $$

Now, writing $p$ as the eigenvalues of momentum in terms of an eigenvalue equation, we have:

$$ -i\hbar \dfrac{\partial}{\partial x} \varphi(x) = p\varphi(x) $$

This is a differential equation that we can in fact solve for $\varphi(x)$ to obtain the solution:

$$ \varphi(x) = e^{ip x / \hbar} $$

We have now found a momentum eigenstate which has a momentum $p$. More generally, by the principle of superposition we saw earlier, this would correspond to a wavefunction given by:

$$ \psi(x) = C_1 e^{ip_1 x / \hbar} + C_2 e^{ip_2 x / \hbar} + \dots + C_n e^{ip_n x / \hbar} $$

Remember that $\psi$ is just the time-independent part of the full wavefunction $\Psi$, which is given by $\Psi(x, t) = \psi(x, t) e^{-iE t/ \hbar}$

The fact that operators represent physical properties is very powerful. For instance, by identification of $\hat H = -\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m} \dfrac{\partial^2}{\partial x^2} + V$ as the left-hand side of the time-independent Schrödinger equation, we have:

$$ \hat H \psi = E\psi $$

And we can similarly write the full (time-dependent) Schrödinger equation as:

$$ i\hbar \dfrac{\partial}{\partial t} = \hat H \psi $$

That is to say, the Schrödinger equation is the eigenvalue equation for the energy operator. This is an incredibly significant statement that we will use extensively going forwards.

Continuous and discrete eigenvalues

So far, we have restricted a lot of our analysis to purely discrete eigenvalues. Let us explore a bit more in this direction, then change course to continuous eigenvalues.

When a system possesses discrete eigenstates (and this is more easily seen with the fact that eigenstates are notated $\varphi_n(x)$) the system is also bounded, meaning that there are (infinite or finite) barriers that confine a particle. The specific feature is that these eigenstates are parametrized by an integer value, so they can be denoted $\varphi_1, \varphi_2, \dots, \varphi_n$. Then the general form of the time-independent wavefunction is given by:

$$ \psi(x) = \sum_n C_n \varphi_n(x) $$

One perhaps unexpected result is that since an infinitely many number of eigenstates is in theory possible, a particle's wavefunction at a specific instant $t$ may not itself be an eigenstate - however, it can always be decomposed into a linear superposition of eigenstates. If having knowledge of Fourier series or reading the differential equation series, this may sound familiar.

For instance, consider the wavefunction $\psi(x) = \Psi(x, 0) = A\left(x^{3}-x\right)$ for $-1 \leq x \leq 1$. This is not an eigenstate, but we may write it in series form, whose individual terms are eigenstates, and from which we can find the ground state and the other eigenstates:

$$ \psi(x) = -\dfrac{16A}{\pi^4} (\pi^2 - 12) e^{i(\pi x/ 2 + \pi/2)} - \dfrac{16A}{81\pi^4}(9\pi^2-12) e^{3i(\pi x/ 2 + \pi/2)} + \dots $$

In the continuous case, which is the case for position and momentum eigenstates, we have an eigenstate for every possible value of the physical quantity, instead of just integers. The position and momentum are examples where we observe continuous eigenstates; they can take a continuous spectrum of values including non-integer values. In addition, instead of discrete probability coefficients $C_n$ whose squares give the probability, we now have a continuous probability coefficient function $C(\lambda)$, where $\lambda$ is a continuous eigenvalue, such as $C(x)$ or $C(p)$ for position and momentum respectively. Therefore, we now have an integral for writing down the general wavefunction in terms of the continuous eigenstates; for momentum eigenstates, we have:

$$ \psi(x) = \int_{-\infty}^\infty C(k) e^{i k x} dk = \int_{-\infty}^\infty C(p) e^{i p x/\hbar} dp $$

Addenum: position eigenstates

Position eigenstates are similar in nature to momentum eigenstates, but they are not discussed as often because position eigenstates run into some complicated technicalities. First, by solving for $\hat x \psi = x \psi$, we can find that the eigenstates are given by $\varphi(x) = \delta(x - x')$ where $\delta$ is the Dirac delta function, which is zero everywhere except for a point $x'$ where the function has a spike. Then the general wavefunction is given by:

$$ \psi(x) = \int_{-\infty}^\infty C(x)\delta(x - x')\, dx $$

But the Dirac delta function obeys the identity:

$$ \int_{-\infty}^\infty f(x)\delta(x - x') dx = f(x) $$

Which means that:

$$ \psi(x) = \int_{-\infty}^\infty C(x)\delta(x - x')\, dx = C(x) $$

We now see that $\psi(x) = C(x)$ - that is to say, the spectrum of probability coefficients for continuous position eigenstates are the wavefunction. This somewhat perplexing result means that there are infinitely-many position eigenstates $\varphi(x) = \delta(x - x')$, one at every point in space, and the wavefunction is just the collection of probability coefficients of all of those eigenstates.

If this is all too abstract, that is completely understandable. We will re-examine the idea of the wavefunction being a probability coefficient function of eigenstates later, when we discuss the Dirac formulation of quantum mechanics.

Expectation values

We have seen that operators represent physical properties (such as position or momentum), that eigenstates are solutions to eigenvalue equations, and that eigenvalues are the possible measurable values of the physical property. We have also seen that a superposition of eigenstates of an operator can be used to write out the wavefunction, and that the probability coefficients $C_n$ in the superposition are related to the probability $|P_n|$ associated with each state.

Recall that the actual properties of a quantum particle are unknown and random, and the best we can do is to predict probabilities. However, just as we can predict the probabilities of the particle being in a particular state through the probability coefficients of each eigenstate, we can predict the average measured value. We call this the expectation value.

In the discrete case, for a given operator $\hat A$ with eigenstates $\varphi_n(x)$, the expectation value is notated $\langle \hat A\rangle$ and is given by:

$$ \langle \hat A\rangle = \sum_n |C_n|^2 A_n $$

Meanwhile, in the continuous case, for a given operator $\hat A$, the expectation value is given by:

$$ \langle \hat A\rangle = \int_{-\infty}^\infty \bar \Psi(x, t) \hat A \Psi(x, t)\, dx $$

In the cases of the position and momentum operators $\hat x = x$ and $\hat p = -i\hbar \dfrac{\partial}{\partial x}$, by substituting into the above formula, the expectation values are given by:

$$ \begin{align*} \langle x \rangle &= \int_{-\infty}^\infty \bar \Psi(x, t) x\, \Psi(x, t) dx \\ \langle p \rangle &= \int_{-\infty}^\infty \bar \Psi(x, t) \left(-i\hbar \dfrac{\partial}{\partial x} \Psi(x, t)\right) dx \end{align*} $$

It may seem strange at first glance that expectation values are not time-dependent (i.e. that we don't also have to integrate with respect to time). The reason, however, is that when a wavefunction and its conjugate are multiplied, the time-components of the wavefunction combine to form $e^{i E t / \hbar}e^{-i E t / \hbar} = 1$.

We may also take the expectation value of a given operator applied twice, which we denote $\langle \hat A^2\rangle$, where $\hat A^2 \varphi = \hat A(\hat A \varphi)$. This notation means that in the discrete case, we have:

$$ \langle \hat A^2\rangle = \sum_n |C_n|^2 A_n {}^2 $$

And in the continuous case we have:

$$ \langle \hat A^2\rangle = \int_{-\infty}^\infty \bar \Psi(x, t) \hat A^2 \Psi(x, t)\, dx $$

Calculating the expectation values further leads to an incredibly important result. From statistical theory, the uncertainty (standard deviation) $\Delta X$ of a given variable $X$ is given by $\Delta X = \sqrt{\langle X^2 \rangle - \langle X \rangle^2}$. This means that in quantum mechanics, for a given physical quantity $A$ which has a corresponding operator $\hat A$, then the uncertainty in measuring $A$ is given by:

$$ \Delta A = \sqrt{\langle \hat A^2 \rangle - \langle \hat A \rangle^2} $$

In the case of the momentum $p$ and position $x$, we obtain the famous result of the Heisenberg uncertainty principle:

$$ \Delta x \Delta p \geq \dfrac{\hbar}{2} $$

The standard deviations $\Delta x$ and $\Delta p$ can be thought of the "spread of measurements", so the Heisenberg uncertainty principle says that the momentum and position eigenvalues cannot both be predicted with certainty. What does this mean in practice? Suppose we had an detector that was purpose-built to measure the momentum and position of a quantum particle. Like any scientific instrument, it has a certain measurement uncertainty, which we will call $\epsilon$. We turn it on, make a position measurement, and then we get a number - perhaps it measures a position of 1.4 nanometers from the measurement device. However, it probably is not exactly at 1.4 nm; since the detector itself has a certain measurement uncertainty, the actual measurement is $\pu{1.4 nm} \pm \epsilon$. We also simultaneously measure the momentum of the particle, and we get another number - perhaps $\pu{5.5e-31 kg*ms^{-1}}$. Conventional wisdom would suggest that the momentum measurement should be $\pu{5.5e-31 kg*ms^{-1}} \pm \epsilon$, just like the position measurement. But the Heisenberg uncertainty principle says that $\Delta x \Delta p \geq \frac{\hbar}{2}$. This means that:

$$ \Delta p \geq \frac{\hbar}{2 \Delta x} \Rightarrow \Delta p \geq \frac{\hbar}{2 \epsilon} $$

So even if the detector's measurement uncertainty $\epsilon$ is made arbitrarily small, the most accurate measurement you can get of the momentum while simultaneously measuring the position is $\pu{5.5 kg*ms^{-1}} \pm \hbar/2\epsilon$. This means that in practice, only one property of a quantum particle can usually be measured to full precision at a time.

A recap

So, to sum up, the fundamental procedure in introductory quantum mechanics is as follows:

- Solve the Schrödinger equation with the appropriate initial and boundary conditions to determine the solutions, which are eigenstates

- For each of the eigenstates, find the probability density function with $\rho(x, t) = |\Psi(x, t)|^2 = \Psi(x, t) \bar \Psi(x, t)$, which yields the probability distribution of the particle in space

- Apply all the operators (Hamiltonian, momentum, angular momentum, etc.) to analyze the different properties of the quantum system being studied. The eigenvalues of each operator are the measurable values of the physical quantity (e.g. energy, momentum, etc.)

- Compute the expectation (average) values of each operator, as well as the uncertainties through $\Delta A = \sqrt{\langle \hat A^2\rangle - \langle \hat A\rangle^2}$

- You may also calculate the probabilities of each eigenstate (and of their associated energy, momentum, and other properties) through $P_n = |C_n|^2$ where $C_n$ is the probability coefficient of the eigenstate in the superposition. This becomes a probability coefficient function $C(\lambda)$ for the continuous spectrum case, which includes $C(x)$ for position and $C(p)$ for momentum.

A brief interlude on spin

For all its predictive power, the simplest form of the Schrödinger equation does not explain one quantum phenomenon: spin. Spin is the property that allows quantum particles like electrons to act as tiny magnets and generate magnetic fields. The name is technically a misnomer: in classical mechanics, a spinning charge would create a magnetic field, but subatomic particles don't actually spin, they just behave as if they did.

To make this idea more concrete, consider an electron placed in a magnetic field $\mathbf{B}$. It would then experience a torque given by $\vec \tau = \vec \mu \times \mathbf{B}$, where $\vec \mu$ is the magnetic moment given by:

$$ \vec \mu = -\dfrac{g_e e}{2m} \mathbf{S} $$

Where $e$ is the electron charge (also called the elementary charge), $m$ is the electron mass, $g_e \approx 2.00232$ is the electron g-factor, and $|S| = \hbar \sqrt{s(s + 1)}$ is the spin angular momentum vector. Here, $s = \pm \frac{1}{2}$ is called the spin quantum number, which we often shorten to spin. Spin explains how some materials are able to act as permanent magnets: the torque caused by their magnetic moments aligns them in the same direction. In this way, they behave just like little (classical) magnets, except their magnetic moments are a consequence of their spin. The alignment of spins amplifies the tiny magnetic fields of each electron strongly enough that we can observe their combined effect as a macroscopic magnetic field.

Spin modifies a quantum state because a quantum state must additionally include information about a quantum particle's spin. For electrons, all spins must either be $+\frac{1}{2}$ (spin-up) or $-\frac{1}{2}$ (spin-down); these are the only two possible spins.

We formulate spin mathematically as an operator, just like energy and momentum. However, unlike the differential operators we've seen, the spin operators $\hat S_x, \hat S_y, \hat S_z$ (there is one for each direction $x, y, z$) are matrices. In the case of elementary fermions (quarks, electrons, and neutrinos) which have spin-1/2 these are specifically expressed as:

$$ \begin{align*} \hat \sigma _{x} &=\dfrac{\hbar}{2}{\begin{pmatrix}0 & 1\\1 & 0\end{pmatrix}}\\ \hat \sigma_{y} & =\dfrac{\hbar}{2}{\begin{pmatrix}0 & -i\\i & 0\end{pmatrix}}\\ \hat \sigma_{z} & =\dfrac{\hbar}{2}{\begin{pmatrix}1 & 0\\0 & -1\end{pmatrix}}\\ \end{align*} $$

The inclusion of spin means that even electrons with otherwise identical eigenstates are not the same; their wavefunctions must also include whether they are spin-up or spin-down. While the Schrödinger equation does not include spin, more advanced formulations of the Schrödinger equation do include the effects of spin, and are essential for very accurate calculations. We will return to spin later at the end.

Solving quantum systems

We will now apply quantum mechanics to solve a variety of quantum systems, to get a feel for how exactly you do quantum mechanics. Note that there are only a few exact solutions to quantum problems, and approximate methods are required for the vast majority of quantum systems, so these should be (with some exceptions) considered idealized systems.

The free particle

The free particle is among the simplest quantum systems that have an exact solution to the Schrödinger equation. It describes a quantum particle in free space is unconstrained by any potential, and thus has zero potential energy. We start from the one-dimensional Schrödinger equation for $V(x) = 0$, for which we may solve for the wavefunction:

$$ \begin{align*} -\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m} \dfrac{\partial^2 \Psi(x, t)}{\partial x^2} + \cancel{V(x)} &= i \hbar \dfrac{\partial \Psi(x, t)}{\partial t} \Rightarrow \\ -\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m} \dfrac{\partial^2 \Psi(x, t)}{\partial x^2} &= i \hbar \dfrac{\partial \Psi(x, t)}{\partial t} \end{align*} $$

If we assume a solution in the form $\Psi(x) = \psi(x) f(t)$, we may substitute to find that:

$$ \begin{align*} \dfrac{\partial^2 \Psi(x, t)}{\partial x^2} &= f(t)\dfrac{d^2 \psi}{dx^2} \\ \dfrac{\partial \Psi(x, t)}{\partial t} &= \psi(x) \dfrac{df}{dt} \end{align*} $$

These are ordinary derivatives because $\psi(x)$ and $f(t)$ are functions of only one variable.

Thus if we substitute these derivatives back into the Schrödinger equation we get:

$$ -\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m} f(t)\dfrac{d^2 \psi}{dx^2} = i \hbar \psi(x) \dfrac{df}{dt} $$

Now dividing both sides by $\psi(x)f(t)$ we have:

$$ \begin{align*} -\dfrac{1}{\psi(x) f(t)}\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m} f(t)\dfrac{d^2 \psi}{dx^2} = \dfrac{1}{\psi(x) f(t)} i \hbar \psi(x) \dfrac{df}{dt} \\ -\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m} \dfrac{1}{\psi(x)}\dfrac{d^2 \psi}{dx^2} = i \hbar\dfrac{1}{f(t)} \dfrac{df}{dt} = \text{const.} \end{align*} $$

If we call the separation constant $E$, we have:

$$ \begin{align*} -\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m} \dfrac{1}{\psi(x)}\dfrac{d^2 \psi}{dx^2} = i \hbar\dfrac{1}{f(t)} \dfrac{df}{dt} = E \Rightarrow \\ -\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m} \dfrac{1}{\psi(x)}\dfrac{d^2 \psi}{dx^2} = E \\ i \hbar\dfrac{1}{f(t)} \dfrac{df}{dt} = E \end{align*} $$

The two ODEs can be rewritten in a more easily-read form as:

$$ \begin{align*} -\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m} \dfrac{d^2 \psi}{dx^2} = E\psi(x) \\ i \hbar\dfrac{df}{dt} = Ef(t) \end{align*} $$

The top differential equation is the time-independent Schrödinger equation we saw before, just with $V(x) = 0$.

We can use the traditional methods of solving first- and second-order differential equations (or just make an educated guess, that's called an ansatz) to find the solutions are:

$$ \begin{align*} \psi(x) &= e^{i k x}, \quad k \equiv \dfrac{\sqrt{2mE}}{\hbar} \\ f(t) &= e^{-i \omega t}, \quad \omega \equiv \dfrac{E}{\hbar} \\ \Psi(x, t) &= \psi(x) f(t) = e^{ikx} e^{-i\omega t} \\ &= e^{ik x - i\omega t} \end{align*} $$

We call this solution a plane-wave solution.

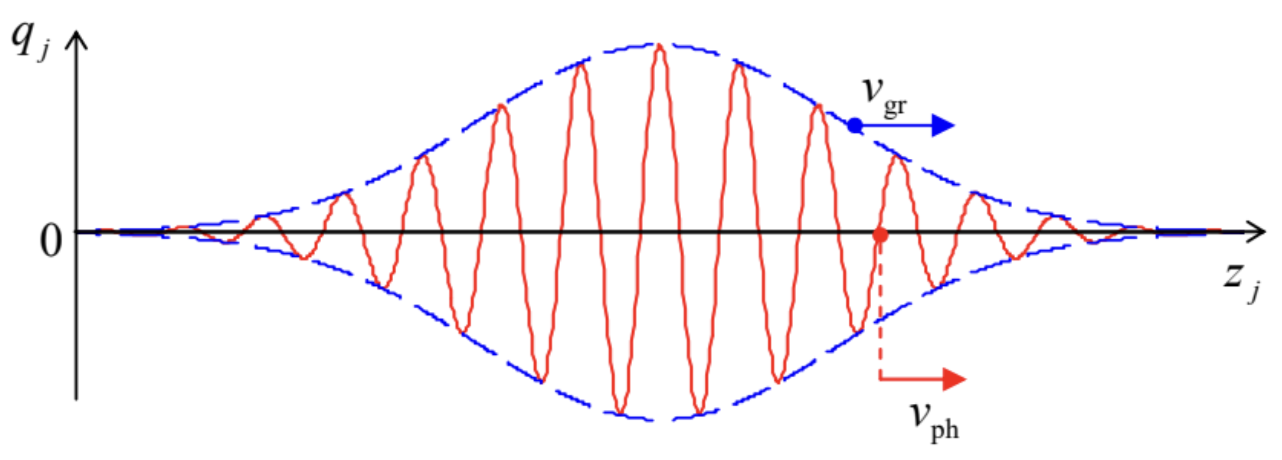

We now encounter an issue: the plane-wave solution $\Psi(x, t) = e^{i(kx -\omega t)}$ is non-normalizable; if we try to perform the normalization integral, we'll find that its total probability is infinite and thus is unphysical. However, if we create a superposition of plane waves by adding them together (which, again, are still solutions to the Schrödinger equation because it is a linear combination), we do get a physical solution, which we call a wave packet:

Source: LibreTexts

We can create this superposition by adding plane waves of different wavevectors $k$ and frequencies $\omega$, which are related by $\omega = k v_g$ where $v_g$ is the group velocity, meaning the velocity at which the wave packet moves over time. This becomes an integral as the number of summed waves approaches infinity:

$$ \Psi(x, t) = \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \int_{-\infty}^\infty A(k) e^{i(kx - \omega t)}\, dk $$

Where $A(k)$ is a function that gives the wavevector $k$ for each summed wave. A common choice of $A(k)$ is the Gaussian, given by:

$$ A(k) = \sqrt{\sigma}\left(\dfrac{2}{\pi}\right)^{1/4} e^{-\sigma^2 (k - k_0)^2} $$

And therefore the wavefunction $\Psi(x, t)$ is given by:

$$ \Psi(x, t) =\left( \dfrac{1}{2 \pi} \right)^{1 / 4} \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{\sigma}} e^{i k_0 x - \frac{x^2}{4 \sigma^2}} e^{-i \omega t} $$

We may calculate the expectation values - that is, the average values - of the free particle's position and momentum. Let us begin with that of position. We have:

$$ \begin{align*} \langle x \rangle &= \int_{-\infty}^\infty \Psi^*(x, t) \hat x \Psi(x, t)\,dx \\ &= \int_{-\infty}^\infty \Psi^*(x, t) x \Psi(x, t)\,dx \\ &= \left[\left( \dfrac{1}{2 \pi} \right)^{1 / 4} \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{\sigma}}\right]^2 \int_{-\infty}^\infty (e^{-ik_0 x}e^{-\frac{x^2}{4\sigma^2}} e^{i\omega t}) x (e^{ik_0 x}e^{-\frac{x^2}{4\sigma^2}} e^{-i\omega t})\, dx \\ &= \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \dfrac{1}{\sigma} \int_{-\infty}^\infty e^{-\frac{x^2}{4\sigma^2}} x e^{-\frac{x^2}{4\sigma^2}}\, dx \\ &= \dfrac{1}{\sigma \sqrt{2\pi}} \int_{-\infty}^\infty xe^{-\frac{x^2}{2\sigma^2}}\, dx \end{align*} $$

The squared quantity in brackets $\left( \dfrac{1}{2 \pi} \right)^{1 / 4} \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{\sigma}}$ that is factored out of the integral is the amplitude from the wavefunction. It is squared because $\psi$ and $\psi^*$ both have this amplitude, and therefore multiplying them together gives a squared amplitude.

However, $xe^{-\frac{x^2}{2\sigma^2}}$ is an odd function. An odd function has $f(-x) = -f(x)$, that is, it flips as you go from $-x$ to $x$, and odd functions satisfy the identity:

$$ \int_{-\infty}^\infty f(x)\, dx = 0 $$

This is because odd functions have a positive area for $x > 0$ and a negative area for $x < 0$ that, once added together, cancel each other out.

Therefore we have:

$$ \langle x \rangle = \dfrac{1}{\sigma \sqrt{2\pi}} \int_{-\infty}^\infty xe^{-\frac{x^2}{2\sigma^2}}\, dx = 0 $$

This means that the particle is most likely to be found at $x = 0$ - which makes sense given that the peak of its wavefunction is located at $x = 0$.

We may also find the expectation value of the momentum. For this, we recall that the momentum expectation value is found by the following equation:

$$ \begin{align*} \langle p\rangle &= \int_{-\infty}^\infty \psi^*(x) \hat p \psi(x)\, dx \\ &= \int_{-\infty}^\infty \psi^*(x) \dfrac{\hbar}{i} \dfrac{\partial}{\partial x} \psi(x)\, dx \\ \end{align*} $$

Note the identity $-i\hbar = \dfrac{\hbar}{i}$. This is why the momentum operator $\hat p$ is sometimes written $\dfrac{\hbar}{i} \dfrac{\partial}{\partial x}$ and sometimes written $-i\hbar \dfrac{\partial}{\partial x}$. They are completely equivalent.

We may find $\hat p \psi$ as follows:

$$ \begin{align*} \hat p \psi &= \dfrac{\hbar}{i} \dfrac{\partial}{\partial x} \\ &= \dfrac{\hbar}{i}\dfrac{\partial}{\partial x}\left[\left( \dfrac{1}{2 \pi} \right)^{1 / 4} \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{\sigma}} e^{i k_0 x - \frac{x^2}{4 \sigma^2}} e^{-i \omega t}\right] \\ &= \dfrac{\hbar}{i} \left( \dfrac{1}{2 \pi} \right)^{1 / 4} \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{\sigma}} e^{-i\omega t} \left[\dfrac{\partial}{\partial x} \left(e^{i k_0 x - \frac{x^2}{4 \sigma^2}}\right)\right] \\ &= \dfrac{\hbar}{i} \left( \dfrac{1}{2 \pi} \right)^{1 / 4} \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{\sigma}} e^{-i\omega t} \left[ \left(ik_0 - \dfrac{x}{2\sigma^2}\right)e^{i k_0 x - \frac{x^2}{4 \sigma^2}}\right] \\ \end{align*} $$

Substituting this expression into the equation for $\langle p\rangle$ we have:

$$ \begin{align*} \langle p\rangle &= \int_{-\infty}^\infty \psi^*(x) \dfrac{\hbar}{i} \dfrac{\partial}{\partial x} \psi(x)\, dx \\ &= \left[\frac{\hbar}{i} \left[\left( \frac{1}{2 \pi} \right)^{1 / 4} \frac{1}{\sqrt{\sigma}}\right]^2 \cancel{e^{i\omega t}e^{-i\omega t}}^{{}^1} \right]\int_{-\infty}^\infty e^{-i k_0 x - \frac{x^2}{4 \sigma^2}} \left(ik_0 - \frac{x}{2\sigma^2}\right)e^{i k_0 x - \frac{x^2}{4 \sigma^2}}\,dx \\ &= \frac{\hbar}{i} \left[\left( \frac{1}{2 \pi} \right)^{1 / 4} \frac{1}{\sqrt{\sigma}}\right]^2 \int_{-\infty}^\infty \cancel{e^{i k_0 x} e^{-ik_0x}}^{{}^1} \left(ik_0 - \frac{x}{2\sigma^2}\right) e^{-\frac{x^2}{4 \sigma^2}}e^{-\frac{x^2}{4 \sigma^2}}\,dx \\ &= \frac{\hbar}{i} \left[\left( \frac{1}{2 \pi} \right)^{1 / 4} \frac{1}{\sqrt{\sigma}}\right]^2 \int_{-\infty}^\infty \left(ik_0 - \frac{x}{2\sigma^2}\right) e^{-\frac{2x^2}{4 \sigma^2}} \,dx \\ &= \frac{\hbar}{i} \left[\left( \frac{1}{2 \pi} \right)^{1 / 4} \frac{1}{\sqrt{\sigma}}\right]^2 \int_{-\infty}^\infty \left(ik_0 - \frac{x}{2\sigma^2}\right) e^{-\frac{x^2}{2 \sigma^2}} \,dx \\ &= \frac{\hbar}{i} \left[\left( \frac{1}{2 \pi} \right)^{1 / 4} \frac{1}{\sqrt{\sigma}}\right]^2 \left(\int_{-\infty}^\infty ik_0 e^{-\frac{x^2}{2 \sigma^2}} \,dx - \int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{x}{2\sigma^2} e^{-\frac{x^2}{2 \sigma^2}} \,dx \right) \end{align*} $$

It is helpful to remember that the conjugate of anything real-valued is itself (e.g. the conjugate of $e^{-\frac{x^2}{2\sigma^2}}$ is itself. Meanwhile, anything complex-valued in the form $e^{\pm i \phi}$ has $e^{\mp i\phi}$ as its conjugate. For instance, $e^{-i\omega t}$ has the conjugate $e^{i\omega t}$, and $e^{-i\omega t} e^{i\omega t} = 1$.

Note, however, that the second integral in the last line of our expression is an odd function, so the integral goes to zero. Therefore, we have the simplified integral (relief!) as follows:

$$ \begin{align*} \langle p \rangle &= \frac{\hbar}{i} \left[\left( \frac{1}{2 \pi} \right)^{1 / 4} \frac{1}{\sqrt{\sigma}}\right]^2 \int_{-\infty}^\infty ik_0 e^{-\frac{x^2}{2 \sigma^2}} \,dx \\ &= \dfrac{\hbar k_0}{\sigma \sqrt{2\pi}} \int_{-\infty}^\infty e^{-\frac{x^2}{2 \sigma^2}} \,dx \end{align*} $$

This is a Gaussian integral that we can solve with the following identity:

$$ \displaystyle \int_{- \infty}^{\infty} e^{- \alpha y^2} d y = \sqrt{\dfrac{\pi}{a}} $$

If we use the substitution that $a = \dfrac{1}{2\sigma^2}$ then we have:

$$ \begin{align*} \langle p \rangle &= \dfrac{\hbar k_0}{\sigma \sqrt{2\pi}} \int_{-\infty}^\infty e^{-\frac{x^2}{2 \sigma^2}} \,dx \\ &= \dfrac{\hbar k_0}{\sigma \sqrt{2\pi}} \sqrt{2\pi \sigma^2} \\ &= \dfrac{\hbar k_0}{\sigma \sqrt{2\pi}} \sigma \sqrt{2\pi} \\ &= \hbar k_0 \end{align*} $$

This is indeed the momentum we expect of a single particle of wavevector $k_0$. While a free particle's momentum can be any eigenvalue of the momentum operator, and cannot be predicted in advance, the average momentum over several measurements $p = \hbar k_0$ is equal to the de Broglie expression for the momentum. Thus, on average, quantum mechanics reduces to deterministic laws.

The infinite square well

Consider a particle that is trapped at a bottom of a well with length $L$ and walls that are infinitely high. We may model this with a potential given by:

$$ V(x) = \begin{cases} \infty, & x < 0 \\ 0, & 0 \leq x \leq L \\ \infty, & x > L \end{cases} $$

The general solution of the time-independent Schrödinger equation is given by:

$$ \psi(x, t) = A e^{i k x} + B e^{-ik x} $$

For some yet-to-be determined constants $A$ and $B$. As the particle is confined within the region $0 \leq x \leq L$, the wavefunction must satisfy the boundary conditions that $\psi(0) = \psi(L) = 0$. By substituting $\psi(0) = 0$ into the equation we have:

$$ \psi(0) = A + B = 0 \Rightarrow B = -A $$

Thus our solution becomes:

$$ \psi(x, t) = A e^{i k x} + (-A) e^{-ik x} = A(e^{i k x} - e^{-ikx}) $$

The, we substitute $\psi(L) = 0$. Therefore we have:

$$ A(e^{i k L} - e^{-ikL}) = 0 $$

We may convert this using Euler's formula to be expressed in terms of trigonometric functions, recalling that $e^{i\theta} - e^{-i\theta} = 2 i\sin \theta$:

$$ A(e^{i k L} - e^{-ikL}) = 2Ai \sin (kL) = 0 $$

Sine is equal to zero at $\theta = 0, \pi, 2\pi, 3\pi, \dots = n\pi$ so we have:

$$ kL = n\pi $$

Which we can rearrange to:

$$ k = \dfrac{n\pi}{L} $$

Thus our solution can now be written as:

$$ \psi(x) = 2A i \sin \left(\dfrac{n\pi x}{L}\right) $$

With associated probability density:

$$ \rho(x) = |\psi(x)|^2 = -4A^2 \sin^2 \left(\dfrac{n\pi x}{L}\right) $$

We may solve for $A$, the normalization factor, by demanding that the integral of the probability density over all space be equal to one:

$$ \int_{-\infty}^\infty \rho(x)\, dx = 1 $$

From here, we can find that $2Ai = \sqrt{\dfrac{2}{L}}$ and therefore the spatial wavefunction is:

$$ \psi(x) = \sqrt{\dfrac{2}{L}} \sin \left(\dfrac{n\pi x}{L}\right) $$

To find the wavefunction in time, we simply apply the Hamiltonian to $\psi$, recalling the $\hat H \psi = E\psi$, where we find that:

$$ \begin{align*} \hat H \psi &= -\frac{\hbar^2}{2m} \dfrac{\partial^2}{\partial x^2} \sqrt{\dfrac{2}{L}} \sin \left(\dfrac{n\pi x}{L}\right) \\ & = \dfrac{n^2 \pi^2 \hbar^2}{2 m L^2} \sqrt{\dfrac{2}{L}} \sin \left(\dfrac{n\pi x}{L}\right) \\ &= E \psi \end{align*} $$

Thus we identify the energies as given by:

$$ E_n = \dfrac{n^2 \pi^2 \hbar^2}{2 m L^2}, \quad n = 1, 2, 3, \dots $$

Note that instead of one energy or a continuous energy spectrum, we have discrete energies $E_1, E_2, E_3, \dots$, one for each integer value of $n$. The $E_1$ state, which is the lowest energy state, is called the ground state. Interestingly, this is nonzero; its energy is given by:

$$ E_1 = \dfrac{\pi^2 \hbar^2}{2 m L^2} $$

This is due to the fact that the energy and momentum operators commute, so that if $E = 0$, then we know the precise energy of the quantum particle (zero) and the precise momentum (also zero). But if the momentum were known precisely (and thus have zero uncertainty), then the Heisenberg uncertainty principle would be violated:

$$ \Delta x \Delta p = \Delta x (0) = 0 \ngeq \dfrac{\hbar}{2} $$

Thus the energy in the ground state cannot be zero; rather, it is a nonzero value we often call the zero-point energy. In addition, since energy can only come in steps of integer $n$, we say that the energy is quantized - hence quantum mechanics.

The zero-point energy is the origin of many physical processes, and is explored in-depth in quantum field theory. It is also of interest in cosmology, where the expansion of the Universe is, according to our best understanding at present, driven by zero-point energy.

The hydrogen atom

A very famous quantum system is that of the hydrogen atom - the simplest atom, with one electron and one proton. We can simplify the system even further by modelling the contribution of the proton with the classical Coloumb charge potential, since the proton is "large enough" compared to the electron (almost a thousand times more massive) that its behavior deviates only slightly from the classical description. Thus, we only need to consider the quantum behavior of the electron for the wavefunction of the entire hydrogen atom system.

Note: In fact, the solution for the hydrogen atom can be generalized to be an exact solution for all hydrogen-like atoms. For instance, it can also be used to solve for the $\ce{He^+}$ atom (helium ion), as well as all the group 1 elements in the periodic table (lithium, sodium, potassium, rubidium, and cesium), ions that have one valence electron (such as $\ce{Ca^+}$ and $\ce{Sr^+}$), and all isotopes of these atoms.

Using the time-independent Schrödinger equation with the Coloumb potential, we have the partial differential equation:

$$ -\frac{\hbar^2}{2m} \nabla^2 \psi - \frac{e^2}{4\pi \varepsilon_0 r} \psi = E \psi $$

This is typically solved in spherical coordinates, where the $\nabla^2$ (Laplacian) operator becomes a mess, resulting in the overwhelmingly long equation (copied from Wikipedia):

$$ -{\frac {\hbar ^{2}}{2m}}\left[{\frac {1}{r^{2}}}{\frac {\partial }{\partial r}}\left(r^{2}{\frac {\partial \psi }{\partial r}}\right)+{\frac {1}{r^{2}\sin \theta }}{\frac {\partial }{\partial \theta }}\left(\sin \theta {\frac {\partial \psi }{\partial \theta }}\right)+{\frac {1}{r^{2}\sin ^{2}\theta }}{\frac {\partial ^{2}\psi }{\partial \varphi ^{2}}}\right]-{\frac {e^{2}}{4\pi \varepsilon _{0}r}}\psi =E\psi $$

The one saving grace is that this PDE happens to be a separable differential equation, and can be solved using separation of variables. But solving this is a matter of mathematics, not physics, and so we will omit the solving steps and just give the general solution:

$$ \psi _{n\ell m}(r,\theta ,\varphi )={\sqrt {{\left({\frac {2}{na_{0}}}\right)}^{3}{\frac {(n-\ell -1)!}{2n(n+\ell )!}}}}e^{-r /2}r^{\ell }L_{n-\ell -1}^{2\ell +1}(r )Y_{\ell }^{m}(\theta ,\varphi ) $$

Where:

- $a_0 = \frac{4\pi \epsilon_0 \hbar^2}{me^2}$ is the Bohr radius, where the electron is most likely to be found in the ground-state hydrogen atom

- $\rho = \frac{2r}{na_0^*}$

- $L_{n - \ell - 1}^{2 \ell + 1}(\rho)$ is a Laguerre polynomial

- $Y_\ell^m (\theta, \varphi)$ is a spherical harmonic function

- $n = 1, 2, 3, \dots$ is the principal quantum number that determines the energy level and parametrizes each eigenstate

- $\ell = 0, 1, 2, \dots, n-1$ is the azimuthal quantum number

- $m = -\ell, \dots, \ell$ is the magnetic quantum number

We can visualize the hydrogen wavefunction (or more precisely, the hydrogen eigenstates) by ploting the probability density:

Source: Sebastian Mag, Medium

The energy levels of hydrogen are given by the energy eigenvalues of its Hamiltonian:

$$ E_n = -\dfrac{\mu e^4}{32\pi^2 \varepsilon_0^2 \hbar^2} \dfrac{1}{n^2} = -\dfrac{\mu c^2 \alpha^2}{2n^2} $$

Which can be written in even simpler form as $E_n = -\dfrac{\mu R_E}{m_e n^2} \approx -\dfrac{R_E}{n^2}$ where $R_E = \dfrac{m_e c^2 \alpha^2}{2}$, known as the Rydberg energy which is approximately $\pu{-13.6 eV}$. In this expression:

- $c$ is the speed of light

- $n$ is the principal quantum number

- $j$ is the total angular momentum quantum number

- $\mu \equiv \dfrac{m_e m_p}{m_e + m_p}$ (where $m_e, m_p$ are the electron and proton mass) is the reduced mass of the hydrogen atom, which is very close to (but not exactly equal to) $m_e$, the mass of an electron

- $\alpha$ is the fine-structure constant and approximately equal to $1/137$

An important note: Yes, these energy eigenvalues are negative, because the Coulomb potential is negative as well. In fact, we say that the negative energies reflect the fact that the associated eigenstates are bound states, and the magnitude of their energy is the energy necessary to overcome the Coulomb potential. As their energies are negative, they do not have enough energy to escape the potential, and thus stay in place - the more negative the energy, the more energy must be put in to "kick" electrons out of place, and the stabler the system.

The historical discovery of the solution to the Schrödinger equation for the hydrogen atom and the calculation of its eigenvalues proved to be one of the first experimental results that confirmed the predictions of quantum mechanics. By using $E_n = \dfrac{hc}{\lambda_n}$ with the value of $E_n = -\dfrac{\mu c^2 \alpha^2}{2n^2}$ predicted by the Schrödinger equation, the calculated wavelengths of light almost exactly matched measurements of those emitted by hydrogen. To read more about this discovery, see the quantum chemistry portion of the general chemistry series. This result revolutionized physics and brought quantum mechanics to its forefront. To this day, quantum mechanics remains the building block of modern physics.

Later on, refinements to quantum theory found that the predicted energy levels, when also including relativistic corrections, are more accurately given by:

$$ \begin{align*} E_{j, n} &= -{\mu c^2}\left[{1 - \left(1 + \left(\dfrac{\alpha}{n - j - \frac{1}{2} + \sqrt{\left(j + \frac{1}{2}\right)^2 - \alpha^2}}\right)^2 \right)^{-1/2}}\right] \\ &= -\dfrac{\mu c^2 \alpha^2}{2n^2} \left[1 + \dfrac{\alpha^2}{n^2} \left(\dfrac{n}{j + 1/2} - \dfrac{3}{4}\right) + \dots\right] \end{align*} $$

Where again, $\mu$ is the reduced mass, $\alpha \approx 1/137$ is the fine-structure constant, and $j_\pm = |\ell \pm \frac{1}{2}|$. Notice that this more accurate expression depends on two integers $n$ and $j$, unlike the non-relativistic expression, which only depends on $n$. However, when we perform a series expansion (shown above), and take only the first-order term, we obtain (as the first term) the energy levels obtained from the Schrödinger equation. We will not derive this ourselves, but we will touch on relativistic quantum mechanics briefly again at the end of this guide.

The quantum harmonic oscillator

We'll now take a look at the quantum harmonic oscillator, a quantum system describing a particle that oscillates within a harmonic (i.e. quadratic) potential. But first, why study it? The reason is because all potentials are approximately harmonic potentials close to their local minimums. Let us see how this gives us powerful tools to solve non-trivial quantum systems.

Consider solving the Schrödinger equation with a non-trivial potential $V(x)$ for some given quantum system. We may expand it as a Taylor series. When the system oscillates about a local minimum of the potential - which, in physical terms, corresponds to having a total energy $E$ slightly above the potential minimum $V_0$ - then the first derivative is approximately zero. The second derivative is a constant, and all higher-order terms vanish. Therefore, the potential can be written as:

$$ V(x) = V(x_0) + \cancel{V'(x_0) x} + \frac{1}{2} V''(x_0) x^2 + \cancel{\frac{1}{6} V'''(x_0) x^3} + \cancel \dots = V_0 + \dfrac{1}{2}kx^2 $$

As the potential energy can be defined against an arbitrarily-chosen reference point, we may add or subtract any constant from the potential without affecting the physics. Thus, we can just as well write the potential as:

$$ V(x) = \dfrac{1}{2} kx^2 $$

If we set $\omega = \sqrt{\frac{k}{m}}$ to be the angular frequency of the oscillations about the potential, then we may rewrite this as:

$$ V(x) = \dfrac{1}{2} m \omega^2 x^2 $$

Ultimately, the point of studying the quantum harmonic oscillator is that for any quantum system constrained to evolve under a potential $V(x)$, their behavior close to a local minimum of the potential will be approximately that of the quantum harmonic oscillator, no matter how complicated the potential is. This greatly increases the number of systems we can find (at least) approximate analytical solutions of.

With all that said, we may now begin solving the Schrödinger equation for the quantum harmonic oscillator. Inserting the harmonic potential into the time-independent Schrödinger equation results in the following PDE:

$$ -\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m} \dfrac{\partial^2 \psi}{\partial x^2} + \dfrac{1}{2} m \omega^2 x^2 \psi = E\psi $$

Given that the solution is dependent only on position we may replace the partial derivatives with ordinary derivatives:

$$ -\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m} \dfrac{d^2 \psi}{dx^2} + \dfrac{1}{2} m \omega^2 x^2 \psi = E\psi $$

This is not an easy differential equation to solve, and finding a solution that describes all the possible states of the quantum harmonic oscillator is highly non-trivial. However, we can make the problem tractable by just solving for the ground state of the quantum harmonic oscillator. By making the assumption that the ground state (being the lowest-energy state) has a very small energy, so $E_0 \psi \approx 0$, the differential equation reduces to:

$$ -\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m} \dfrac{d^2 \psi}{dx^2} + \dfrac{1}{2} m \omega^2 x^2 \psi = 0 $$

We may now algebraically rearrange the differential equation into the form:

$$ \dfrac{d^2 \psi}{dx^2} = \dfrac{m^2 \omega^2}{\hbar^2} x^2 \psi $$

Now note that this can be rewritten as:

$$ \dfrac{d^2 \psi}{dx^2} = \left(\dfrac{m \omega}{\hbar}\right)^2 x^2 \psi $$

If we define a constant $k_s \equiv \dfrac{m \omega}{2\hbar}$ - the physical meaning of this constant will be discussed later - then we can write this as:

$$ \dfrac{d^2 \psi}{dx^2} = k_s^2 x^2 \psi $$

To understand why we do this, we can do some dimensional analysis. The units of $\dfrac{m\omega}{\hbar}$ on the right-hand side of the differential equation are those of inverse squared meters, that is, $\pu{m^{-2}}$. We know of a quantity that has units of inverse meters - the wavevector $k$ - so therefore $\dfrac{m\omega}{\hbar}$ must be proportional to the square of the wavevector. Thus we write $k_s \propto k^2$, with some undetermined proportionality constant.

Recalling that $p = \hbar k$ and therefore $p^2 = \hbar^2 k^2$, we may rearrange to $k^2 = \dfrac{p^2}{\hbar^2}$. But also recalling that $E = \dfrac{p^2}{2m}$ we can rearrange this to find that $p^2 = 2mE$ and thus $k^2 = \dfrac{2mE}{\hbar^2}$. However, we also know another expression for the energy - $E = \hbar \omega$, so if we substitute this in, we have

$$ k^2 = \dfrac{2m\hbar \omega}{\hbar^2} = \dfrac{2m \omega}{\hbar} $$

This is almost there, but not quite - there is the additional factor of two. This is why we include the factor of $1/2$.

Proceeding from the prior steps, we may consider a solution ansatz in the form:

$$ \psi = A e^{-k_s x^2} = Ae^{-\left(\frac{m\omega}{2\hbar}\right) x^2} $$

where $A$ is some undetermined normalization factor. All of what we have done so far is just an (educated) guess - that is the essence of the ansatz technique - but it is the right guess, because if we proceed from this assumption, it can be shown that we get the correct results, and had we guessed wrong we could've just chosen another guess.

If we substitute this ansatz into the Hamiltonian, we find that:

$$ \begin{align*} \hat H \psi &= -\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m} \dfrac{d^2 \psi}{dx^2} + \dfrac{1}{2} m \omega^2 x^2 \psi \\ &= -\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m}\dfrac{d^2}{dx^2} \left(Ae^{-k_s x^2}\right) + \dfrac{1}{2} m \omega^2 x^2 \left(Ae^{-k_s x^2}\right) \\ &= -\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m} (4 k_s^2 x^2 - 2k_s)Ae^{-k_s x^2} + \dfrac{1}{2} m \omega^2 x^2 \left(Ae^{-k_s x^2}\right) \\ &= \left(-\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m} (4 k_s^2 x^2 - 2k_s) + \dfrac{1}{2} m \omega^2 x^2\right)Ae^{-k_s x^2} \\ &= \left(-\dfrac{4\hbar^2}{2m}\frac{m^2\omega^2}{4\hbar^2} x^2 + \dfrac{2\hbar^2}{2m} \frac{m\omega}{2\hbar} + \dfrac{1}{2}m\omega^2 x^2\right)Ae^{-k_s x^2} \\ &= \left(-\dfrac{1}{2}m\omega^2 x^2 + \dfrac{2\hbar^2}{2m} \frac{m\omega}{2\hbar} + \dfrac{1}{2}m\omega^2 x^2\right)Ae^{-k_s x^2} \\ &= \dfrac{1}{2} \hbar \omega Ae^{-k_s x^2} \\ &= \dfrac{1}{2}\hbar \omega \psi \\ &= E \psi \end{align*} $$

Thus our ansatz does satisfy the Schrödinger equation $\hat H \psi = E\psi$, showing that our solution is indeed valid (even if we had to take some very wild guesses to get there!) We do still need to normalize it, however, to ensure the solution is physical (which also automatically satisfies the boundary conditions of the problem $\psi(-\infty) = \psi(\infty) = 0$). Applying the normalization condition we have:

$$ \begin{align*} \int_{-\infty}^\infty \psi^*(x)\psi(x)\, dx &= \int_{-\infty}^\infty Ae^{-k_s x^2} Ae^{-k_s x^2} dx \\ &= A^2 \int_{-\infty}^\infty e^{-2k_s x^2} dx \\ &= A^2\sqrt{\dfrac{\pi}{2k_s}} \end{align*} $$

Where we solved the integral using the Gaussian integral identity:

$$ \int_{-\infty}^\infty e^{-a x^2} = \sqrt{\dfrac{\pi}{a}} $$

For probability to be conserved, we must have the $A^2\sqrt{\dfrac{\pi}{2k_s}} = 1$, using which we can solve for $A$:

$$ \begin{gather*} A^2\sqrt{\dfrac{\pi}{2k_s}} = 1 \\ A^2 = \sqrt{\dfrac{2k_s}{\pi}} \\ A = \left(\dfrac{2k_s}{\pi}\right)^{1/4} \end{gather*} \\ A = \left(\dfrac{m\omega}{\pi \hbar}\right)^{1/4} $$

So the ground state of the quantum harmonic oscillator is given by:

$$ \psi_0 = \left(\dfrac{m\omega}{\pi \hbar}\right)^{1/4} e^{-\left(\frac{m\omega}{2\hbar}\right) x^2} $$

Furthermore, we note that this solution for the ground state of the quantum harmonic oscillator has energy eigenvalue $E_0 = \dfrac{1}{2}\hbar\omega$. The general expression for the energy eigenvalues of the quantum harmonic oscillator are given by:

$$ E_n = \left(n + \dfrac{1}{2}\right)\hbar \omega $$

For which we can see that with $n = 0$ we have the familiar expression of $E = \dfrac{1}{2} \hbar \omega$. What about the general expression for the wavefunction, you might ask? Well, it is given by:

$$ \psi_n(x) = \left(\dfrac{m\omega}{\pi \hbar}\right) \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2^n n!}} H_n\left(\sqrt{\dfrac{m\omega}{\hbar}}x \right) \exp\left(-\dfrac{m\omega x^2}{2\hbar}\right) $$

Where $n$ is the principal quantum number (as with the hydrogen atom), and $H_n(x)$ is an $n$-th order Hermite polynomial, which are a set of special functions, much like the Laguerre polynomials used in the wavefunction of the hydrogen atom. We show some plots of the quantum harmonic oscillator wavefunction for different below:

Source: Wikipedia

Understandably, considering the fact that the most general solution can only be expressed in terms of special functions, we started by solving only for the ground state, not the general case for all energy levels!

The mathematics behind quantum mechanics

The Schrödinger equation is certainly a very useful tool and all problems in non-relativistic quantum theory, with the exception of problems that involve spin, can be solved from the Schrödinger equation. However, simply taking the Schrödinger equation for granted is ignoring why it works the way it does. So we will now take many steps back and build up quantum theory from its mathematical and physical fundamentals.

Postulate 1: quantization

When a quantitiy is said to be quantized, it cannot take on continuous values; it can only come in discrete steps. In addition, all possible values of that quantity must be an integer multiple of some base indivisible value.

For example, consider electrical charge. The base value of electric charge is the elementary charge constant $e$ (not to be confused with Euler's number), associated with a single electron. It is only possible for an object in the universe to have a charge of $1e, 2e, 3e, \dots ne$. It is not possible for an object to have a charge of $3.516e$.

Note to the advanced reader: yes, indeed, quarks have a different quantum of charge, but since quarks can never be found on their own, and are always grouped together into composite, not elementary particles, we consider $e$ the quantum of charge, associated with an electron.

Similarly, consider electromagnetic radiation. The base value of electromagnetic energy is given by $hf = \dfrac{hc}{\lambda}$, the radiation of a single photon of frequency $f$ and wavelength $\lambda$, where $h = \pu{6.626e-34 J*Hz^{-1}}$ is the Planck constant. All electromagnetic energy of a given frequency $f$ and wavelength $\lambda$ must be composed of multiples of this value.

Postulate 2: quantum states

In classical mechanics, the future state of any system of particles can be known by knowing its current state and its equations of motion. The equations of motion are Newton's 2nd law:

$$ m \frac{d^2 \mathbf{r}}{dt^2} = \mathbf{F}(\mathbf{r}, t) $$

Which can be rewritten as system of 2 coupled first-order ODEs:

$$ \begin{align*} \frac{d\mathbf{p}}{dt} = \mathbf{F}(\mathbf{r}, t) \\ m \frac{d\mathbf{r}}{dt} = \mathbf{p} \end{align*} $$

The initial condition for this system is the classical state of the particle, and is the following 6-component vector, consisting of three components of position and three components of momentum:

$$ \mathbf{X}_0 = \begin{pmatrix} x_0 \\ y_0 \\ z_0 \\ p_{x_0} \\ p_{y_0} \\ p_{z_0} \end{pmatrix} $$

In quantum mechanics, the current state of a system is described with a quantum state-vector. This is typically written abstractly as a complex vector $|\Psi\rangle$ whose components are complex numbers, with the specialized notation (called bra-ket or Dirac notation) used to differentiate quantum states from classical states.

Note on notation: in bra-ket notation, all vectors are denoted with the right angle-bracket $| V \rangle$, and a scalar multiplication of a vector is written $a | V \rangle$.

Quantum state-vectors can be hard to understand, so it is worth taking some time to get to know them. Recall that ordinary Cartesian vectors in the form $\langle x, y, z \rangle$ can be written in terms of the Cartesian basis vectors $\hat i, \hat j, \hat k$:

$$ \mathbf{V} = V_x \hat i + V_y \hat j + V_z \hat k $$

We can alternatively denote the Cartesian basis vectors with $\hat e_x, \hat e_y, \hat e_z$, in which notation the same vector can be written as:

$$ \mathbf{V} = V_x \hat e_x + V_y \hat e_y + V_z \hat e_z $$