Fundamentals of Chemistry

This page is print-friendly. Simply press Ctrl + P (or Command + P if you use a Mac) to print the page and download it as a PDF.

Table of contents

Note: it is highly recommended to navigate by clicking links in the table of contents! It means you can use the back button in your browser to go back to any section you were reading, so you can jump back and forth between sections!

- A high-level introduction to chemistry

- The quantum origins of chemistry

- The chemistry lexicon

- Modern atomic theory

- Periodic table

- Covalent compounds

- Molar calculations, molarity, and stoichiometry

- Ionic compounds

- Acids and bases

- Solubility and aqueous reactions

- The quantum theory of the atom

- Paramagnetism, diamagnetism and ferromagnetism

- The Lewis model of chemical bonding

- VSEPR theory and bond geometries

- Valence bond theory

- Organic chemistry

- Types of organic compounds

- Alcohols

- The kinetic theory of gases

- Thermochemistry

This is a mini-book covering the topics of a typical general chemistry course, including atomic structure, the theory of reactions, chemical equations, stoichiometry, Lewis theory, and a brief introduction to quantum chemistry. Additional topics covered include valence bonding theory, VSEPR theory, the kinetic theory of gases, and energy changes within reactions.

I owe a debt of gratitude to Professor Steven Tysoe of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute for his instruction and permission to share this with everyone, and I have tried to ensure there are as few sentences copied verbatim from his lecture materials as possible. There is no need for attribution for redistributing this mini-book in part of in whole, and they may be freely used for commercial purposes. In fact, I release it to the public domain (dual licensed with Creative Commons CC0, whichever is more permissive in the given jurisdiction) so that it belongs to everyone. Copy from it, study from it, and give it to others freely and without limits - I would welcome that!

Note: this does not apply to some of the separately-licensed external assets, including images and tables, which have license information attached separately.

In these notes, there is general information as well as optional asides for more advanced/interested readers that are not important for studying general chemistry. Read the asides only if interested, otherwise, just read the main content.

A high-level introduction to chemistry

Chemistry is the empirical (evidence and experimentally-based) study of the matter and the interactions of matter that analyzes the microscopic properties of matter to describe its macroscopic behavior.

While physics is usually on the scale of generally big life-sized things (projectiles, rockets, trains), very big things (black holes, galaxies, the entire universe even) or very very small things (elementary particles like electrons and quarks), chemistry analyzes things on the scale of atoms and molecules, and up to compounds and materials, that generally form a bigger whole.

Stability (that is, descent to a lower energy state that is more stable) and conservation (quantities that do not change) are essential to chemistry. In addition, the behavior of electrons is essential to understanding chemical interactions. This is because electrons are the mediators of the electromagnetic interaction and therefore responsible for all chemistry (other than nuclear chemistry). Armed with this knowledge, we can explain the rich and diverse landscape of chemistry.

The quantum origins of chemistry

Fundamental chemistry comes from the quantum world that governs matter on the atomic and subatomic scales. Atoms constitute the fundamental building blocks of ordinary matter. Therefore, atoms and the structures they form are the main objects of study in chemistry.

Atoms are not the only important factor in the chemical properties of matter. For instance, graphite and diamond are both composed of carbon atoms, but their differing arrangement of electrons results in greatly different macroscopic properties.

As a high-level overview, matter is anything that occupies space (more technically, a cross-sectional area in which it interacts) and has mass. The structure and composition of matter determines its properties. In addition, the energy present in matter determines its state and structure. Energy is divided into two general types, kinetic energy and potential energy (energy that is stored in some thing and capable of being released). In chemistry, kinetic energy measured macroscopically typically takes the form of thermal energy (heat) and potential energy measured macroscopically typically takes the form of chemical energy.

Note for the advanced reader: Chemical energy, which we can broadly speak of as energy stored in chemical bonds, is actually the sum of the individual electromagnetic potential energies associated with each of the electrons in matter. Quantum chemistry provides quantitative methods to describe chemical energy in terms of potential surfaces and atomic wavefunctions, but this is far beyond the scope of a general chemistry course.

The chemistry lexicon

An intensive property is a characteristic that is intrinsic to a substance, but an extensive property can vary based on how much of the substance there is.

Significant figures are the proper way to record scientific measurement, which involves writing a value in terms of a value and an uncertainty in the form of limited precision, such as $3.57 \pm 0.005\ \pu{kg}$. Significant figures ignore leading zeroes and round after a certain number of digits, truncating the rest and (often) writing an uncertainty to represent the fact that values were omitted.

Accuracy and precision are not identical in chemistry and have specific meanings. Accuracy is how well a measurement can be made to ensure that it is as close as possible to the real value. Precision is a measure of the spread of a measurement.

Units are a prerequisite for doing chemistry. The SI system of measurement is the predominant unit system used in science, but regardless of what unit is used, you should never report a measurement without units (unless if the quantity is dimensionless).

Modern atomic theory

Modern atomic theory regards substances according to three key observations of nature:

- The conservation of mass - no mass is created or destroyed within a chemical reaction

- The law of definite proportions - the reactants participating in a chemical reaction are proportional to their products and furthermore these ratios must be whole positive numbers

- The law of multiple proportions - the ratios of reactants to products in chemical reactions are fixed ratios no matter the quantities involved in the reaction; this means you can scale up the amounts of reactants but the formulas and laws describing the reaction will stay the same

Note: the law of the conservation of mass takes a different form in relativistic quantum chemistry, in which case mass and energy may be converted into each other, and mass posseses intrinsic energy.

The chemist John Dalton was one of the originators of atomic theory. He recognized that elements do not magically turn into each other; rather they participate in chemical reactions that change the compounds they form. Chemist J. J. Thomson proved the existence of electrons as particles that are inside of atoms. Rutherford's gold foil experiment found that electrons are negatively charged, and that the nucleus is positively charged, and eventually it was formed that neutral neutrons as well as positively-charged protons made up of the nucleus. Elements are identified by the atomic number $Z$ which is the number of protons within the atom, as well as the atomic mass $A$ which is the sum of the number of protons and number of neutrons as given in atomic mass units $\pu{amu}$. We therefore notate an element with $\ce{^A_Z S}$ where $S$ is the element name. For instance, $\ce{^4_2 He}$ denotes the helium atom, with an atomic mass of 4 (2 protons and 2 neutrons) and an atomic number of 2 (because of its two protons).

Due to the equal and opposite charges of electrons as compared to protons, there are equal numbers of electrons and protons in a neutral atom, so that atoms are generally electrically neutral and thus stable. However, the same element can have different numbers of neutrons; variations of the same element are called isotopes and are important for nuclear chemistry and nuclear physics. One common example is uranium, which has several well-known isotopes, uranium-238 denoted $\ce{^{238}_{92} U}$, and uranium-235 denoted $\ce{^{235}_{92} U}$.

Periodic table

The periodic table categorizes the properties of all known elements. All elements are represented by a specific chemical symbol, such as $\ce{Cu}$ for copper, $\ce{Fe}$ for iron, and $\ce{C}$ for carbon. The original periodic table was able to predict the properties of 2 then-unknown elements. The phenomena that allows the periodic table to exist is called periodicity, where repeating groups of elements share the same chemical properties. This is caused by the arrangement of valence (outermost) electrons, which are the same in elements of the same group. For example, the alkali metals (sodium, potassium, cesium, etc. referred together as group I) all have one valence electron.

While it is possible to find naturally-occuring substances containing only one element, most chemical substances are composed of compounds. Compounds are formed by chemical bonds between atoms of different elements. As an example, water, with the chemical formula $\ce{H2O}$, is composed of hydrogen and oxygen atoms. There are three main types of basic compounds: covalent compounds, ionic compounds, and metallic compounds. We will now examine covalent and ionic compounds in more detail.

Covalent compounds

Covalent compounds formed by nonmetals are generally covalent compounds held together by covalent bonds. In covalent bonding, two atoms overlap and share electrons, creating molecules.

Naming conventions for covalent compounds

- Start with the element furthest to the left of the periodic table

- Name the second element with the -ide suffix, and a greek prefix based on the number of that second element in the chemical formula:

- mono- for one (typically not used when naming the first element)

- di- for two

- tri- for three

- tetra- for four

- pent- for five

- hexa- for six

- e.g. $\ce{O_2}$ is dioxide (e.g. in $\ce{CO2}$ which is carbon dioxide)

Note that this process can be done in reverse to find the molecular formula for a covalent compound. E.g. carbon dioxide has the molecular formula $\ce{CO2}$ because the first element is carbon, which by convention is one carbon when not specified, and dioxide with the di- prefix denotes two oxygen atoms.

Molar calculations, molarity, and stoichiometry

A mole is a key unit used in chemistry, denoted $\pu{mol}$. It denotes a specific amount of units of something. It is chemically relevant because mol of an element's atoms has a mass in grams equal to the atoms' atomic mass. For instance, because (pure) carbon $\ce{^12_6 C}$ has an atomic mass of $\pu{12 amu}$, 1 mol of carbon atoms has a mass of 12 grams. More generally, for $N$ moles of atoms of a particular element:

$$ M_\pu{grams} = N_\pu{mol} \cdot \frac{M_\pu{amu}}{\pu{1 mol}} $$

If we explicitly write out the units, we have:

$$ \pu{Mass in grams} = \pu{Number of moles} \cdot \pu{Mass in amu} \cdot \frac{\pu{gram}}{\pu{mol}} $$

We can define a new quantity called the molar mass, in units of grams per mole, as follows:

$$ M_\mathrm{molar} = M_\mathrm{amu} \cdot \pu{grams/mol} $$

Given that carbon $\ce{^12_6 C}$ has an atomic mass of $\pu{12 amu}$, its molar mass is $\pu{12 g/mol}$. This is technically only true for pure carbon-12; while $\ce{^12_6 C}$ is the most common isotope of carbon, there are other carbon isotopes as well, so carbon has an atomic mass of $\pu{12.011 amu}$ and thus the molar mass of carbon is $\pu{12.011 g/mol}$. Using the molar mass allows us to easily find the mass in grams for any element given the known amount of that element in moles.

The molar mass for compounds can be written as combinations of the molar mass of the constituent elements:

$$ M_\mathrm{molar} = \sum_i M_i^{(\mathrm{molar})} $$

For instance, the molar mass of water, $\ce{H2O}$, is equal to the sum of the molar masses of its two hydrogen atoms and the molar mass of the oxygen atom. By calculation, we can find that $M_{\ce{H2O}}^{(\mathrm{molar})} = 2 \cdot M_{\ce{H}}^{(\mathrm{molar})} + M_{\ce{O}}^{(\mathrm{molar})} = 2 \cdot 1.008 + 15.999 \approx \pu{18.015 g/mol}$. Therefore, one mole of water molecules would have a mass of $\pu{18.015g}$. How many atoms are there in a mole? The answer is a preposterously big number, called Avogadro's number:

$$ N_A = 6.02214076 \times 10^{23}\, \frac{\pu{units}}{\pu{mol}} $$

Using the mole as a unit is greatly useful for calculating quantities of substances involved in a chemical reaction. Consider the combustion of hydrogen, $\ce{2H2(g) + O2(g) -> 2H2O(g)}$. The equation can be expressed directly in formula units: 2 moles of hydrogen gas reacts with 1 mole of oxygen gas to produce 2 moles of water. This formula can be scaled up and down with different numbers of moles, but the coefficients remain in fixed ratios and thus one needs to multiply all the coefficients by the scaling factor (say, 2 for the reaction quantities scaled up $\times 2$) and find the moles of reactants required and products produced.

In addition, molar units offer an efficient way to measure the concentration of solutions. The molarity is the number of moles per unit volume, in units of $\pu{M}$ which is a unit equivalent to $\pu{mol/L}$ (we use the fact that $\pu{1L} = \pu{1 dm^3} = \pu{1000cm^3}$). Thus converting formula units as expressed in chemical equations is straightforward, as formulas units are already given in units of moles.

Given the molarity, we can also make calculations to convert quantities between diluted and concentrated versions of the same solution. Dilution is simply reducing the molarity of a solution. A solution concentrated at molarity $M_1$ and volume $V_1$ is related to the same solution concentrated at molarity $M_2$ and volume $V_2$ follows the following relationship:

$$ M_1 V_1 = M_2 V_2 $$

Which can be used to solve for any one of $M_1, M_2, V_1, V_2$ given the parameters of the problem. Finally, we may derive chemical formulas from empirical measurements of an unknown chemical substance. We start from the data of each constituent element as a percent of the unknown substance's mass. This is the percent mass which is denoted here as $M_\%$. Then, we can find the number of moles of each constituent element by dividing the percent mass with the molar mass of each element:

$$ n_\mathrm{moles} = \dfrac{M_\%}{M^{\mathrm{element}}_{(\mathrm{moles})}} $$

By finding the ratio of the number of moles of each constituent element, we can find the chemical formula. For instance, a substance with $\pu{0.66 mol}$ of hydrogen and $\pu{0.33 mol}$ of oxygen would have a hydrogen-oxygen ratio of $2:1$ and thus the chemical formula would be $\ce{H2O}$, that is, water.

Note: which elements are present in a sample is often determined by atomic spectroscopy. More on that later.

We can also find the chemical formula similarly when we just know the masses of each element. To do so, we find the number of moles by dividing the measured mass (typically in grams) by the known molar mass of each element. Consider, for instance, that we knew a sample contained a certain number of grams of a certain element. We can find the number of moles of that element within the sample by the formula:

$$ n_\mathrm{moles} = \dfrac{M_\mathrm{grams}}{M_\mathrm{molar}} $$

And then find the ratios of the number of moles of each element to determine the chemical formula. Remember this is not the same thing as the ratio of their masses. Different elements (as well as different compounds) have different molar masses, and therefore you must first find the number of moles of each constituent element.

A similar process applies for chemical reactions. Consider the photosynthesis/respiration reaction:

$$ \ce{C6H12O6} + \ce{6O2} \Leftrightarrow \ce{6H2O} + \ce{6CO2} $$

Here, we have 1 mol of glucose ($\ce{C6H12O6}$) reacting with 6 moles of oxygen to make 6 moles of hydrogen and 6 moles of carbon dioxide, a ratio of $1:6:6:6$. We can use the same methods as above to calculate the amount of reactant necessary to make a certain quantity of reaction products, and vice-versa.

To do so, let's we first find the total quantity of reaction products that can be made from a given amount of glucose. The formula to calculate this is as follows:

$$ n_\text{moles (product)} = n_\text{moles (reactant)} \cdot \frac{N_P}{N_R} $$

Where $N_P$ is the number of moles of the reaction product produced for every $N_R$ moles of reactant. We can find this from the coefficients of the balanced chemical equation we just wrote down: we know that for every 1 mol of glucose, 6 mol of water and 6 mol of carbon dioxide are produced. Thus, $N_P/N_R = 6$ for both water and carbon dioxide, because 6 mol of each is produced from 1 mol of glucose. That is to say:

$$ \begin{align*} n_\mathrm{moles (\ce{CO2})} = n_\mathrm{moles (\ce{C6H12O6})} \cdot \frac{\ce{6 mol CO2 produced}}{\ce{1 mol C6H12O6 used}} \\\\ n_\mathrm{moles (\ce{H2O})} = n_\mathrm{moles (\ce{C6H12O6})} \cdot \frac{\ce{6 mol H2O produced}}{\ce{1 mol C6H12O6 used}} \end{align*} $$

While not the case for this reaction, we sometimes find that a certain reactant cannot produce as many moles of reaction product than another reactant. The reactant that can produce less moles of product is then known as a limiting reactant, and the reactant that can produce more moles of product is known as an excess reactant.

The limiting reactant determines the theoretical yield, the idealized amount of product produced in a chemical reaction. In actuality, due to losses in reactions, the actual amount of product is usually less than the theoretical yield. Thus, we define a percent yield given by $\dfrac{\text{actual yield}}{\text{theoretical yield}} \cdot 100$. The percent yield by definition is always less than 100%, and the theoretical yield is always higher than the percent yield. If this is not the case, it is likely that a calculation error was made.

Ionic compounds

Ionic compounds are compounds formed by the transfer of electrons between ions. In ionic bonding, an electron (or several) is transferred from a positively-charged ion to a negatively-charged ion, creating a structured lattice. Ions are atoms or combinations of atoms that have a net electric charge.

Note for the advanced reader: ions have a precise description via electromagnetic theory, which can be used to analyze the fundamental electromagnetic interactions of ions by their interaction through the microscopic electric field. However, in general chemistry, we will only describe ions on a macroscopic level.

The word "molecule" applies technically only to covalent compounds. Ionic compounds do not form molecules because their atoms are arranged in lattices in which there is no distinct separation between bonded atoms.

Tables of ions

In general, alkali metals and alkaline earth metals have only one type of cation. The following table lists monatomic cations of metals that generally form only one cation:

| Metal | Cation | Metal | Cation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lithium | $\ce{Li^+}$ | Scandium | $\ce{Sc^{3+}}$ |

| Sodium | $\ce{Na^+}$ | Aluminium | $\ce{Al^{3+}}$ |

| Potassium | $\ce{K^+}$ | Zinc | $\ce{Zn^{2+}}$ |

| Rubidium | $\ce{Rb^+}$ | Silver | $\ce{Ag^+}$ |

| Cesium | $\ce{Cs^+}$ | Magnesium | $\ce{Mg^{2+}}$ |

| Calcium | $\ce{Ca^{2+}}$ | Strontium | $\ce{Sr^{2+}}$ |

| Barium | $\ce{Ba^{2+}}$ |

Table replicated from Chemistry: A Molecular Approach, Pearson, Chapter 3.5, Figure 3.7. Shared under Fair Use.

Other metals can form different cations, and thus the type of cation must be specified, such as $\ce{FeO}$ denoted iron(II) oxide as opposed to simply iron oxide, because the specific cation of iron that forms iron(II) oxide is the $\ce{Fe^{2+}}$ ion. Some examples of cations of common metals that have more than one cation are shown in the table below:

| Metal | Cation | Cation Name |

|---|---|---|

| Chromium | $\ce{Cr^{2+}}$ | Chromium(II) |

| Chromium | $\ce{Cr^{3+}}$ | Chromium(III) |

| Iron | $\ce{Fe^{2+}}$ | Iron(II) |

| Iron | $\ce{Fe^{3+}}$ | Iron(III) |

| Cobalt | $\ce{Co^{2+}}$ | Cobalt(II) |

| Cobalt | $\ce{Co^{3+}}$ | Cobalt(III) |

| Copper | $\ce{Cu^+}$ | Copper(I) |

| Copper | $\ce{Cu^{2+}}$ | Copper(II) |

| Tin | $\ce{Sn^{2+}}$ | Tin(II) |

| Tin | $\ce{Sn^{4+}}$ | Tin(IV) |

| Mercury | $\ce{Hg_2^{2+}}$ | Mercury(I) |

| Mercury | $\ce{Hg^{2+}}$ | Mercury(II) |

| Lead | $\ce{Pb^{2+}}$ | Lead(II) |

| Lead | $\ce{Pb^{4+}}$ | Lead(IV) |

Table replicated from Chemistry: A Molecular Approach, Pearson, Chapter 3.5, Table 3.3. Shared under Fair Use.

Non-metals can also often form multiple different anions, but some of the most common are shown in the table below:

| Non-metal | Anion | Anion Name |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorine | $\ce{F^-}$ | Fluoride |

| Chlorine | $\ce{Cl^-}$ | Chloride |

| Bromine | $\ce{Br^-}$ | Bromide |

| Iodine | $\ce{I^-}$ | Iodide |

| Oxygen | $\ce{O^{2-}}$ | Oxide |

| Sulfur | $\ce{S^{2-}}$ | Sulfide |

| Nitrogen | $\ce{N^{3-}}$ | Nitride |

| Phosphorus | $\ce{P^{3-}}$ | Phosphide |

Table replicated from Chemistry: A Molecular Approach, Pearson, Chapter 3.5, Table 3.2. Shared under Fair Use.

Finally, ions are sometimes composed of multiple atoms, and a table of these polyatomic ions is given below:

| Name | Formula | Name | Formula |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetate | $\ce{C2H3O2}^-$ | Carbonate | $\ce{CO3}^{2-}$ |

| Hydrogen carbonate (bicarbonate) | $\ce{HCO3}^-$ | Hydroxide | $\ce{OH}^-$ |

| Nitrite | $\ce{NO2}^-$ | Nitrate | $\ce{NO3}^-$ |

| Chromate | $\ce{CrO4}^{2-}$ | Dichromate | $\ce{Cr2O7}^{2-}$ |

| Phosphate | $\ce{PO4}^{3-}$ | Hydrogen phosphate | $\ce{HPO4}^{2-}$ |

| Dihydrogen phosphate | $\ce{H2PO4}^-$ | Ammonium | $\ce{NH4}^+$ |

| Hypochlorite | $\ce{ClO}^-$ | Chlorite | $\ce{ClO2}^-$ |

| Chlorate | $\ce{ClO3}^-$ | Perchlorate | $\ce{ClO4}^-$ |

| Permanganate | $\ce{MnO4}^-$ | Sulfite | $\ce{SO3}^{2-}$ |

| Hydrogen sulfite (bisulfite) | $\ce{HSO3}^-$ | Sulfate | $\ce{SO4}^{2-}$ |

| Hydrogen sulfate (bisulfate) | $\ce{HSO4}^-$ | Cyanide | $\ce{CN}^-$ |

| Peroxide | $\ce{O2}^{2-}$ |

Table replicated from Chemistry: A Molecular Approach, Pearson, Chapter 3.5, Table 3.4. Shared under Fair Use.

Naming conventions for ionic compounds

Ionic compounds have simpler naming conventions as opposed to covalent compounds. The naming convention is simply the name of the cation followed by the name of the anion; the units name of the anion are not necessary (for instance, there is no need to use dichloride for $\ce{MgCl2}$, simply chloride) because specifying the cation and anion uniquely determines the chemical formula. One simply writes the cation name followed by the anion, such as magnesium chloride for $\ce{MgCl2}$ and iron(II) sulfate for $\ce{FeSO4}$.

Acids and bases

Acids and bases are some of the most common chemical substances. The simplest theory of acids and bases is Arrhenius theory. A more accurate theory is the later Brønsted–Lowry theory We will examine both.

The Arrhenius definition of an acid is a compound that releases hydrogen ions $\ce{H^+}$ when dissolved in water, and is typically denoted $\ce{aq}$ in chemical reactions (it stands for aqueous, i.e. a solution where water is the solver). The extent to which ionization occurs determines the strength of the acid. Hydrogen ions, which are single protons, form hydronium ions $\ce{H3O^+}$ in water, and the concentration of hydronium, notated $[\ce{H3O^+}]$, determines the $\ce{pH}$ of the solution by the following relationship:

$$ \ce{pH} = - \log [\ce{H3O^+}], \quad [\ce{H3O^+}] = 10^{-\ce{pH}} $$

The Arrhenius definition of a base is a compound that releases hydroxide ions $\ce{OH^-}$ when dissolved in water. Bases are also aqueous. The $\ce{pOH}$ of a solution, which obeys $\ce{pOH + pH = 14}$, is used to quantify the concentration of hydroxide ions, and is determined as follows:

$$ \ce{pOH} = - \log [\ce{OH^-}], \quad [\ce{OH-}] = 10^{-\ce{pOH}} $$

When studying acids and bases, it is useful to think of the $\ce{H2O}$ molecule as $\ce{(H^+)-(OH^-)}$, i.e. a hydrogen ion bonded to a hydroxide ion.

We observe, however, many substances that act like acids or bases but are not technically acids or bases under the Arrhenius definitions. A more useful and modern definition of acids and bases is given by Brønsted-Lowry theory. The Brønsted-Lowry definition of an acid is any substance that donates protons, while the Brønsted-Lowry definition of a base is any substance that accepts (receives) protons.

Given the revised definitions of acids and bases in Brønsted-Lowry theory, we observe some curious results. For instance, some substances can act both as an acid and as a base, which we call amphoteric. An example is water, which autoionizes into $\ce{H+}$ and $\ce{OH-}$ ions. Thus we say that in water, there is both a donation of protons ($\ce{H+}$) and reception of protons by $\ce{OH-}$.

In addition, acids and bases come in pairs in Brønsted-Lowry theory. Consider sulfuric acid, $\ce{H2SO4}$, which, when dissolved in water, releases $\ce{H+}$ protons, resulting in the formation of hydrogen sulfate $\ce{HSO4-}$. Since $\ce{HSO4-}$ differs from $\ce{H2SO4}$ by a single electron, we call hydrogen sulfate the conjugate base of sulfuric acid. Thus, $\ce{H2SO4}$ and $\ce{HSO4-}$ together form a conjugate acid-base pair.

Note that this section is only a brief overview of some topics relevant to studying acids and bases. We will return to discussions on acids and bases when we discuss chemical equilibria as well as titrations.

Solubility and aqueous reactions

Solutions and their formation

We observe that when many ionic compounds are placed into water, they dissolve and form an (aqueous) solution, which we label as $\ce{aq}$ in chemical reactions. When this happens, their constituent ions dissociate and the solution becomes filled with cations and anions. The ionic compounds that are soluble can be determined through the following empirical solubility rules:

| Compound contains | Result | Exceptions |

|---|---|---|

| $\ce{Li^+, Na^+, K^+, NH4^+}$ ion | Soluble | None |

| $\ce{NO3^-, C2H3O2^-}$ ion | Soluble | None |

| $\ce{Cl^-, Br^-, I^-}$ ion | Soluble | Insoluble when any one of $\ce{Ag^+, Hg2^{2+}, Pb^{2+}}$ are present |

| $\ce{SO4^{2-}}$ ion | Soluble | Insoluble when any one of $\ce{Sr^{2+}, Ba^{2+}, Pb^{2+}, Ag^+, Ca^{2+}}$ are present |

| $\ce{OH^-, S^{2-}}$ ion | Insoluble | Soluble when: case 1) any one of $\ce{Li^+, Na^+, K^+, NH4^+}$ are present, case 2) when $\ce{S^{2-}}$ in addition to $\ce{Ca^{2+}, Sr^{2+}, Ba^{2+}}$ are present, or case 3) when $\ce{OH^-}$ in addition to $\ce{Ca^{2+}, Sr^{2+}, Ba^{2+}}$ are present (but in this case, only slightly soluble) |

| $\ce{CO3^{2-}}$ | Insoluble | Soluble when any one of $\ce{Li^+, Na^+, K^+, NH4^+}$ are present |

Based on Table 5.1, Chapter 5, Chemistry: A Molecular Approach 6th Edition by Pearson.

Precipitation reactions

A precipitation reaction occurs between two soluble ionic compounds that react to form a new insoluble ionic compound. This, in fact, is the only case that a precipitation reaction occurs; it must be in the form:

$$ \text{soluble solution } + \text{soluble solution } \to \text{insoluble product} $$

That is to say, a precipitation reaction must be a reaction between two soluble ionic compounds and must form an insoluble compound, as determined through the table above. When a precipitation reaction occurs, the newly-formed insoluble compound emerges ("precipitates") out of the solution, as it is insoluble. The precipitate is a solid and floats at the top of the solution.

Ionic equations

Consider the reaction between potassium hydroxide $\ce{KOH}$ and copper(II) chloride $\ce{CuCl2}$. The balanced chemical equation is:

$$ \ce{2KOH(aq) + CuCl2(aq) \to 2KCl(aq) + Cu(OH)2(s)} $$

To better showcase the ionic nature of the reaction, we can write each aqueous solution in the chemical equation in terms of the constituent ions (any liquid, solid, or gaseous terms don't count, only the aqueous terms are separated into their constituent ions). The complete ionic equation describing the reaction is given by:

$$ \begin{align*} \ce{2K^+(aq) + 2OH^-(aq) + Cu^{2+}(aq) &+ 2Cl^-(aq)} \to \\ \ce{2K^+ (aq) &+ 2Cl^-(aq) + Cu(OH)2(s)} \end{align*} $$

Note that we only decomposed the constituent ions in the aqueous terms. The solid precipitate is left untouched because it does not consist of free ions in solution.

Complete ionic equations, however, are often very verbose. One of the main reasons why is that they include spectator ions, which don't change through the reaction and occur on both sides of the equation. For instance, in the above complete ionic equation, we see that $\ce{2K^+}$ and $\ce{2Cl^-}$ occur on both sides of the equation. Therefore, we consider them spectator ions. By removing all the spectator ions from both sides of the equation, we obtain the net ionic equation:

$$ \ce{2OH^-(aq) + Cu^{2+}(aq) \to Cu(OH)2(s)} $$

Titrations and acid-base reactions

A titration is a type of reaction that can be used to determine the concentration of a sample based on its reaction products. To do so, we react the unknown sample with a sample of known concentration, slowly adding more and more amounts of the sample of known concentration until no more can react, which we refer to as reaching the equivalence point.

As a demonstrative calculation, consider the reaction between a sample of hydrochloric acid $\ce{HCl (aq)}$ of unknown concentration and sodium hydroxide solution $\ce{NaOH(aq)}$. The balanced chemical equation is:

$$ \ce{HCl(aq) + NaOH(aq) \to NaCl(aq) + H2O(l)} $$

We know the ratio of moles of product to moles of each individual reactant from the chemical equation. That is to say, 1 mol of $\ce{HCl}$ reacts with 1 mol of $\ce{NaOH}$ to form 1 mol of $\ce{NaCl}$ (we can choose either reaction product to set up the ratios, as long as we are consistent and use the same reaction product for both reactants). Then we have:

$$ M_\ce{HCl} = \dfrac{\ce{1 mol NaCl produced}}{\ce{1 mol NaOH used}} \times M_\ce{NaOH} \times V_\ce{NaOH} $$

Where $M_\ce{HCl}$ is the concentration of $\ce{HCl}$ we want to determine, and $M_\ce{NaOH}$ and $V_\ce{NaOH}$ are the known concentration and volume of the $\ce{NaOH}$ solution respectively. We may use a similar technique with other reactions.

Oxidation states and redox reactions

The pure forms of all elements are composed of electrically-neutral atoms, as they have the same number of electrons as their protons. The number of protons is fixed for atoms of a particular element. However, due to chemical processes, atoms may have extra electrons or missing electrons, making them no longer electrically neutral. We describe this extra or lack of electrons via an oxidation state. A +1 oxidation state means a +1 charge, that is, one missing electron, while a -1 oxidation state means a -1 charge, that is, one extra electron.

Equations that involve electron transfer from one atom to another are known as redox reactions. In a redox reaction, there are (at least) two reactants present: one is a oxidizer (oxidizing agent), and one is a reducer (reducing agent). A reducer loses electrons (reduces its number of electrons) by donating them to the oxidizer, which gains electrons. Therefore, the oxidation state of a reducer increases due to losing electrons while the oxidation state of the oxidizer decreases due to gaining electrons. These results are summarized in the following table:

| Reactant | Electron transfer type | Oxidation state | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidizer | Gain (accept) electrons | Decrease | $\ce{Cl ->[+ {e^-}] Cl-}$ |

| Reducer | Lose/"reduces" electrons | Increase | $\ce{Na ->[-{e^-}] Na^+}$ |

By virtue of their ability to lose electrons, reducers donate electrons in a chemical reaction. Common reducers include the alkali-metal-based compounds and hydrogen-based compounds, but are not limited to these. Meanwhile, oxidizers readily accept electrons from reducers. Common oxidizers include the halogens, hydrogen peroxide, and yes, oxygen as well as halogen-based compounds and oxygen-based compounds. Oxidizers can be thought of as "electron-stealers" that take electrons from other atoms.

In a redox reaction, we may write the complete reaction as a combination of two half-reactions, one being the oxidation half-reaction and one being the reduction half-reaction. Consider, for instance, the combustion of hydrogen gas (a reducer) in oxygen (an oxidizer). This is the familiar reaction:

$$ \ce{2H2(g) + O2(g) -> 2H2O(g)} $$

This is in fact a redox reaction, even if it may not appear to be so. Each hydrogen atom loses an electron and each oxygen atom gains two electrons. Thus we have the two half-reactions given by:

$$ \begin{align*} &\ce{H ->[-{e^-}] H^+} \\ &\ce{O ->[+{2e^-}] O^{2-}} \end{align*} $$

Two hydrogen cations then combine with one oxygen anion to form the water molecule:

$$ \ce{2H^+ + O^- -> H2O} $$

This completes the reaction, forming water. However, the reaction can also easily be reversed if water becomes ionized, that is, split into its constituent ions. Given that hydrogen is a strong reducing agent and oxygen is a strong oxidizing agent, water spontaneously ionizes itself to a certain degree. Full ionization can be done through electrolysis where electricity is used to ionize water, allowing recovery of oxygen and hydrogen gas by the reverse reaction:

$$ \ce{2H2O(l)} + \pu{285.8 kJ} \ce{-> 2H2(g) + O2(g)} $$

Note, however, that this is a reaction that needs energy put in to occur. We will discuss such types of reactions, known as endothermic reactions, in the thermochemistry section.

The quantum theory of the atom

When matter interacts with electromagnetic radiation, it emits light in a very specific pattern called an emission spectrum, referred to simply as a spectrum for this section. Every element has a unique spectrum and only emits light at particular wavelengths, which are referred to on a spectrum as spectral lines. Therefore, spectroscopy, the study of spectrums, can be used to determine the elements present from any source from simply measuring the spectral lines.

The emission spectrum of hydrogen (source: Wikimedia)

The quantum nature of fundamental chemistry is the basis of all chemistry and its behavior. It explains results that cannot be explained classically, like the periodicity of the elements (which makes the periodic table possible), why certain elements are metals and others not, ionization, and why reactivity can vary between elements. This is because several important differences from classical theory is present in quantum theory:

- Electrons possess discrete energies. Further, electrons can only have an energy equal to a fixed energy level (known as an electron shell). This is known as quantization.

- Electrons change energy levels $E_1 \to E_2$, releasing a photon in the process with an energy equal to the difference between energy levels $\Delta E$.

The quantum nature of light

In the early 20th-century it was found that light exhibited unusual properties, behaving wave-like in some circumstances and particle-like in other circumstances. This is the principle of wave-particle duality. It is important to emphasize that light is not a wave, and light is not a particle. It is something else, a separate category, that is neither wave nor particle but has characteristics of both waves and particles.

In addition, our familiar sense of "light", that being visible light, constitutes only a small fraction of the electromagnetic spectrum. The energy of a single photon of light is given by $E = hf = \dfrac{hc}{\lambda}$ where $h = \pu{6.626E-34 J*Hz^{-1}}$ is the Planck constant. Therefore, the higher the frequency of a photon, the higher the energy. The highest energy light comes in the form of very-short-wavelength high-frequency gamma rays, with X-rays that closely follow, and UV after; these have so much energy that they can ionize atoms by transferring so much energy that they can strip atoms of their electrons, and thus are dangerous to be exposed to. At nanometer wavelengths we have visible light and UV light, which is light that carries heat radiated by objects due to their temperature. Photons interact with electrons and transfer their energy to electrons, which ultimately results in the chemical behavior of different elements and compounds. A reproduced list of the subdivisions of light present within the entire electromagnetic spectrum is shown below:

| Spectrum of light | Approximate wavelength range |

|---|---|

| Radio waves | $\lambda > \pu{0.01 m}$ (anything above $\pu{1 cm}$) |

| Microwaves | $\pu{10^{-4} m} < \lambda < \pu{10^{-2}m}$ ($\pu{0.1 mm}$ to $\pu{1 cm)}$ |

| Far infrared | $\pu{10^{-5} m} < \lambda < \pu{10^{-4} m}$ ($\pu{10 \mu m}$ to $\pu{0.1 mm}$) |

| Middle infrared | $\pu{2E-6 m < \lambda < \pu{1E-5}m}$ ($\pu{2000 nm}$ to $\pu{10 \mu m}$) |

| Near infrared | $\pu{8E-7 m} < \lambda < \pu{2E-6 m}$ ($\pu{800 nm}$ to $\pu{2000 nm}$) |

| Visible | $\pu{4E-7 m} < \lambda < \pu{8E-7 m}$ ($\pu{400 nm}$ to $\pu{800 nm}$) |

| Near ultraviolet | $\pu{2E-7 m} < \lambda < \pu{4E-7 m}$ ($\pu{200nm}$ to $\pu{400nm}$) |

| Far ultraviolet | $\pu{1E-8m} < \lambda < \pu{2E-7}$ (10 nm to 200nm) |

| Gamma ray | $\lambda < \pu{1E-8 m}$ (anything shorter than 10 nm) |

The Schrödinger equation

The Schrödinger equation is a partial differential equation studied extensively in quantum physics, as it describes the quantum nature of electrons in an atom. It takes the form:

$$ i\hbar \dfrac{\partial}{\partial t}\Psi = -\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m} \nabla^2\Psi + V(x, y, z)\Psi $$

While the equation itself and how to solve it are not necessary to know for general chemistry, the eigenstate solutions of the Schrödinger equation give the energy levels of electrons within an atom, and is the origin of the Rydberg formula:

$$ \dfrac{1}{\lambda} = R_H \left(\dfrac{1}{{n_f}^2} - \dfrac{1}{{n_i}^2}\right) $$

This is the formula that predicts the wavelengths of emission spectra from the transition of energy levels, where $R_H$ is the hydrogen Rydberg constant, $n_i$ is the initial energy level of an electron, and $n_f$ is its energy level after the transition.

Each solution to the Schrödinger equation is known as a wavefunction, a complex-valued function whose squared absolute value represents the probability per unit volume of an electron occupying that location. These solution wavefunctions are characterized by three quantum numbers, $n, \ell, m_s$, which, along with a fourth number, $s$, that have special significance in quantum chemistry:

| Number name | Symbol | Physical interpretation | Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principal quantum number | $n$ | The number associated with an energy level of an electron. | $n \geq 1$ |

| Azimuthal quantum number also called angular momenum quantum number | $\ell$ | The number associated with the shape and angular spread of the electron's probability distribution, and also the orbital angular momentum of the electron. | $0 \le \ell \le n -1$ (where $n$ is the principal quantum number) |

| Magnetic quantum number | $m_\ell$ | The number associated with the orientation of the electron, and contributes to the magnetic moment that decides how an electron aligns with a magnetic field. | $-\ell \le m_\ell \le \ell$ (where $\ell$ is the azimuthal quantum number) |

| Spin quantum number (a later extension, not in the original solution) | $s$ | The number associated with the $z$ component of the spin angular momentum, a distinct form of angular momentum carried by subatomic particles, and also contributes to the magnetic moment. | $s = \pm \dfrac{1}{2}$ (for electrons) |

Note for the very advanced reader: the spin quantum number does not describe actual spinning particles, but rather, the phase transformation $e^{i\theta} \to e^{i \theta + d\theta}$ that denotes a rotation about the complex plane. Since the complex-valued wavefunction describing electrons from the Dirac equation $i\hbar \gamma^\mu \partial_\mu \psi - mc \psi = 0$ has a Dirac spinor solution $\psi \sim e^{-ipx}$, and thus as the wavefunction evolves, its phase revolves about the complex plane. The angular momentum depends on the phase, producing the effect of spin as a form of angular momentum without any actual spinning, one that is distinct from classical notions of angular momentum and only found in subatomic particles.

We have a specific notation for characterizing electrons by their azimuthal quantum number $\ell$, based on its value:

| Value of $\ell$ | Orbital name |

|---|---|

| 0 | $s$ orbital |

| 1 | $p$ orbital |

| 2 | $d$ orbital |

| 3 | $f$ orbital |

| 4 | $g$ orbital |

For an orbital of $n = 1, \ell = 0$ for instance, we would call it a $1s$ orbital, which is the ground state (lowest energy state) of hydrogen. For an orbital of $n = 2, \ell = 0$ we would call it a $2s$ orbital, and similarly, for an orbital of $n = 2, \ell = 1$ we would call it a $2p$ orbital. This notation is convenient for describing the precise electron configuration we are referring to. Electrons transition to a higher-energy orbital instantaneously upon absorbing a photon; this is called an excited state. Then, electrons descend to a lower-energy orbital by releasing the excess energy in the form of a photon with the same amount of energy, explaining the spectral lines seen on a spectroscope.

Note for the reader: rather than $1s, 2s, 2p, \dots$ an alternative notation is ${^1}S, {^2}S, {^2}P, \dots$

The solution of the Schrödinger equation for hydrogen is of particular interest, because an exact solution can be found. This allows prediction of many quantum properties of the hydrogen atomic in particular and all atoms in general. First, the solution predicted that when an electron undergoes a transition between orbitals, it emits a photon of wavelength $\lambda$, where $\lambda$ is given by the Rydberg formula, just as we discussed earlier:

$$ \dfrac{1}{\lambda} = R_H \left(\dfrac{1}{n^2_\mathrm{after}} - \dfrac{1}{n^2_\mathrm{initial}}\right) $$

Where $n_\mathrm{initial}, n_\mathrm{after}$ are the principal quantum numbers (more on this later) of the initial orbital and the post-transition orbital, respectively. Then the energy of the emitted photon can be found via $E = \dfrac{hc}{\lambda}$, as before. The predictions of the emission spectra matched those measured experimentally through spectroscopy, confirming the quantum theory.

Multielectron atoms do not have an analytical solution by the Schrödinger equation. However, there are approximate methods that can be used to understand their behavior. First, multielectron atoms have orbitals of different energy, known as sublevel energy splitting. This makes the orbitals non-degenerate, meaning that they don't have the same energy. Three effects are primarily responsible for this: Coulomb force interactions between electrons, shielding by interior electrons, and penetration in the absence of shielding. The outermost electrons, known as the valence electrons, are the primary electrons responsible for the chemical interactions of atoms. The elements with the same number of valence electrons have the same chemical properties, a phenomenon known as periodicity and is the basis for why the periodic table makes such accurate predictions about elements.

The situations in which the standard quantum model fails

Recall that the aforementioned quantum analysis uses approximate methods for multi-electron atoms. This is not always guaranteed to work. For many transition metals, the $3d$ and $4s$ orbitals have energy levels that are very close together and thus the precise electron configuration cannot be determined by theory and must be determined experimentally through spectroscopy. For these it is best to simply reference a text on the specific electron configurations. In addition, even otherwise-identical orbitals are additionally split into slightly different orbitals, creating what is known as fine structure and hyperfine structure. For instance, in hydrogen, we have the $2p_{1/2}$ and $2s_{1/2}$ split energy levels that have slightly different energies, a phenomenon known as the Lamb shift, one of the most famous predictions of the theory of quantum electrodynamics, which makes more accurate predictions than the Schrödinger equation. A visual of this sublevel energy splitting is shown below:

Source: Wikipedia by user ReyHahn

Electron orbitals and configuration

In an atom, electrons have quantized energy levels and can occupy only one energy level at a time. Due to historical reasons, we call these energy levels electron orbitals, though electrons do not truly "orbit" in any real sense. Electrons, however, can enter and leave energy levels, emitting or receiving a photon in the process, a photon that has the same energy as the difference in the energies between the electron orbitals.

Electrons are found in electron shells, which are specific energy levels that are quantized. Each electron shell is associated with each value of the principal quantum number $n$. For instance, $n = 1$ would be the first shell, $n = 2$ would be the second, $n = 3$ would be the third, and so on. Electron shells also have subshells within them, that contain further subdivisions of energy levels. Each subshell depends not only on the principal quantum number $n$, but also on the azimuthal quantum number $\ell$. Similarly to electron shells, electron subshells come in a specific order: $\ell = 0$ is the first subshell, $\ell = 1$ is the second subshell, $\ell = 2$ is the third subshell, and so forth. An orbital is specified by a combination of the electron shell and the subshell within the electron shell. For instance, the $1s$ orbital would be the first shell, $s$ subshell, and therefore have the quantum numbers $n = 1, s = 0$. The $3d$ orbital would be the third shell, $d$ subshell, and therefore have the quantum numbers $n = 3, d = 2$.

All orbitals of the same subshell (that is, if either are both $s$, both $p$, both $d$, both $f$, or both $g$ orbitals) have the same number of electrons. While they are larger, their electrons are generally further from the nucleus, and their probability density functions have more nodes in their 3D shapes, they always have the same number of electrons. The rules for subshells are as follows:

- $s$ subshells can contain at most two electrons

- $p$ subshells can contain at most six electrons

- $d$ subshells can contain at most ten electrons

- $f$ subshells can contain at most fourteen electrons

- $g$ subshells contain the rest (at most eighteen)

Each subshell fixes the $n$ and $\ell$ quantum numbers but still allows electrons to be differentiated based on their $m_\ell$ and $s$ quantum numbers. The magnetic quantum number $m_\ell$ specifies the projection of the orbital angular momentum $L_z$ along the $z$ axis by $L_z = m_\ell \hbar$. Meanwhile, the spin, which is another form of angular momentum, can take either one of spin-up or spin-down states (so two possible values). Since no two electrons in an atom may have the same set of four quantum numbers, which is known as the Pauli Exclusion Principle, all orbitals must have electrons with opposite spin. Therefore, we can subdivide orbitals as follows:

- Each atom has distinct energy levels that electrons may have. Each energy level is called an electron shell and is characterized by the principal quantum number $n$.

- Within each electron shell, there are distinct orbital angular momenta that electrons may have. Each possible value of orbital angular momentum is called a subshell and is characterized by the orbital angular momentum quantum number $\ell$, in addition to the principal quantum number $n$.

- Within each subshell, there are distinct orientations of angular momenta that electrons may have. Each possible value of orientation is called an orbital and is characterized by the magnetic quantum number $m_\ell$, in addition to the principal and orbital angular momentum quantum numbers $n, \ell$.

- Within each orbital, there are different spins that electrons must have, which means that electrons may only come individually or in pairs of opposite spin. Thus, each electron shares its orbital with at most one other electron of opposite spin (although it could also be a lone electron). So each electron is characterized by its spin quantum number $s$ as well as $n, \ell, m_\ell$.

Electron configurations

To describe the orbials of atoms, we write them via electron configurations, where we list out each orbital of an atom. To do so, we follow the Aufbau principle, which gives the order that orbitals are filled as follows:

Source: Wikipedia

That is to say, an element's atoms contain as many orbitals as are needed to hold all its electrons, and orbitals are filled in the following order:

$$ \begin{gather*} 1s^2 \to 2s^2 \to 2p^6 \to 3s^2 \to 3p^6 \to 4s^2 \to 3d^{10} \\ \to 4p^6 \to 5s^2 \to 4d^{10} \to 5p^6 \to 6s^2 \dots \end{gather*} $$

For convenience, we often abbreviate the electron configuration by writing it relative to the closest noble gas (as we'll see, noble gases have relatively easy-to-determine electron configurations). For instance, lithium has the electron configuration $1s^2 2s^1$ which can also be written in terms of helium, the closest noble gas, which has electron configuration $1s^2$, as $\ce{[He]} 2s^1$. Below are the electron configurations of some common elements:

| Element | Symbol | Atomic number | Electron configuration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen | $\ce{H}$ | 1 | $1s^1$ |

| Helium | $\ce{He}$ | 2 | $1s^2$ |

| Lithium | $\ce{Li}$ | 3 | $1s^2 2s^1$ |

| Carbon | $\ce{C}$ | 6 | $1s^2 2s^2 2p^2$ |

| Nitrogen | $\ce{N}$ | 7 | $1s^2 2s^2 2p^3$ |

| Oxygen | $\ce{O}$ | 8 | $1s^2 2s^2 2p^4$ |

| Fluorine | $\ce{F}$ | 9 | $1s^2 2s^2 2p^5$ |

| Neon | $\ce{Ne}$ | 10 | $1s^2 2s^2 2p^6$ (perfect 2, 8 octet) |

| Sodium | $\ce{Na}$ | 11 | $\pu{[Ne]} 3s^1$ |

| Magnesium | $\ce{Mg}$ | 12 | $\ce{[Ne]}3s^2$ |

| Aluminum | $\ce{Al}$ | 13 | $\ce{[Ne]}3s^2 3p^1$ |

| Silicon | $\ce{Si}$ | 14 | $\ce{[Ne]} 3s^2 3p^2$ |

| Phosphorus | $\ce{P}$ | 15 | $\ce{[Ne]} 3s^2 3p^3$ |

| Sulfur | $\ce{S}$ | 16 | $\ce{[Ne]} 3s^2 3p^4$ |

| Chlorine | $\ce{Cl}$ | 17 | $\ce{[Ne]} 3s^2 3p^5$ |

| Argon | $\ce{Ar}$ | 18 | $\ce{[Ne]} 3s^2 3p^6 = 1s^2 2s^2 2p^6 3s^2 3p^6$ (perfect 2, 8, 8 octet) |

| Potassium | $\ce{K}$ | 19 | $\ce{[Ar]} 4s^1$ |

| Calcium | $\ce{Ca}$ | 20 | $\ce{[Ar]} 4s^2$ |

| Scandium | $\ce{Sc}$ | 21 | $\ce{[Ar]}4s^2 3d^1$ |

| Titanium | $\ce{Ti}$ | 22 | $\ce{[Ar]}4s^2 3d^2$ |

| Chromium | $\ce{Cr}$ | 24 | $\ce{[Ar]} 4s^1 3d^5$ |

| Iron | $\ce{Fe}$ | 26 | $\ce{[Ar]} 4s^2 3d^6$ |

| Cobalt | $\ce{Co}$ | 27 | $\ce{[Ar]}4s^2 3d^7$ |

| Nickel | $\ce{Ni}$ | 28 | $\ce{[Ar]} 4s^2 3d^8$ |

| Copper | $\ce{Cu}$ | 29 | $\ce{[Ar]} 4s^1 3d^{10}$ |

| Zinc | $\ce{Zn}$ | 30 | $\ce{[Ar]} 4s^2 3d^{10}$ |

| Bromine | $\ce{Br}$ | 35 | $\ce{[Ar]} 4s^2 4p^5$ |

| Krypton | $\ce{Kr}$ | 36 | $\ce{[Ar]} 4s^2 4p^6 = 1s^2 2s^2 2p^6 3s^2 3p^6 4s^2 4p^6$ (perfect 2, 8, 18, 8 octet) |

| Silver | $\ce{Ag}$ | 47 | $\ce{[Kr]} 5s^1 4d^{10}$ |

| Xenon | $\ce{Xe}$ | 54 | $\ce{[Kr]} 5s^2 5p^6 = 1s^2 2s^2 2p^6 3s^2 3p^6 4s^2 4p^6 5s^2 5p^6$ (perfect 2, 8, 18, 18, 8 octet) |

| Platinum | $\ce{Au}$ | 79 | $\ce{[Xe]} 6s^1 5d^9$ |

| Gold | $\ce{Au}$ | 79 | $\ce{[Xe]} 6s^1 5d^{10}$ |

Based on Mastering Chemistry Textbook. Shared under Fair Use.

Exceptions to the Aufbau principle

While it is possible to deduce the electron configurations of most elements using the Aufbau principle, there are certain exceptions. Recall that energy levels scale as $1/n^2$ so higher electron shells are closer together. This means that electrons of higher orbitals readily move into other higher orbitals, leading to the following elements having unusual electronic configurations:

| Element | Symbol | Electron configuration |

|---|---|---|

| Copper | $\ce{Cu}$ | $\ce{[Ar]} 3d^{10} 4s^1$ |

| Silver | $\ce{Ag}$ | $\ce{[Kr]} 4d^{10} 5s^1$ |

| Gold | $\ce{Au}$ | $\ce{[Xe]} 4f^{14} 5d^{10} 6s^1$ |

| Palladium | $\ce{Pd}$ | $\ce{[Kr] 4d^{10}}$ |

| Chromium | $\ce{Cr}$ | $\ce{[Ar]} 3d^5 4s^1$ |

| Molybdenum | $\ce{Mo}$ | $\ce{[Kr]} 4d^5 5s^1$ |

These must be determined experimentally and memorized or looked up in a reference handbook.

Periodicity from electron configuration

With a few exceptions, the electrons that participate in chemical reactions are only the outermost shell (valence shell) electrons, known as the valence electrons. All other electrons are known as core electrons and have little to no effect in chemical reactions. The number of valence electrons can be found directly from the electron configuration, and a fully-filled valence shell is a very stable configuration that minimizes the potential energy of the atom. Therefore, chemical reactions occur frequently for atoms to be able to gain or lose the required number of electrons to attain a fully-filled valence shell, creating ions. A pattern emerges when we write out the valence shells that attain a full outer shell for atoms of $n = 1, 2, 3, \dots$ electron shells:

| Number of shells | Valence shell (including all subshells) | Number of valence electrons |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | $1s^2$ | 2 |

| 2 | $2s^2 2p^6$ | 8 |

| 3 | $3s^2 3p^6$ | 8 |

| 4 | $4s^2 4p^6$ | 8 |

| 5 | $5s^2 5p^6$ | 8 |

| 6 | $6s^2 6p^6$ | 8 |

Due to the pattern of electron orbitals, the number of electrons required to attain a fully-filled valence shells repeats across elements. For instance, fluorine, chlorine, iodine, and bromide all have a valence shell with 7 electrons, and thus need to gain one electron to form a full shell. Therefore, these elements form the anions $\ce{F-}, \ce{Cl-}, \ce{I-}, \ce{Br-}$ and all are of $-1$ charge. This means that these elements behave very similarly in chemical reactions - indeed, we group these elements together as the halogens. Given that the number of valence electrons required for a fully-filled valence shell is (other than for the first shell) always eight, elements in the periodic table repeat in blocks, and form ions with predicable charges. The halogens, for instance, always form a $-1$ charge ion, the alkali metals always form a $+1$ charge ion, the alkali earth metals always form a $+2$ charge ion, and so on. Elements that are close to having a fully-filled valence shell are highly reactive, but elements relatively far from having a fully-filled valence shell (e.g. carbon, nitrogen) are relatively unreactive. Elements that already have a fully-filled valence shell (the noble gases) are very unreactive and participate very little in chemical reactions.

Shielding, penetration, and atomic radii

Recall that Coulomb interactions are responsible for the non-degeneracy (separate) energy levels of subshells. We define the effective nuclear charge as the nuclear charge (that is, total charge of all the protons) added to the combined electron charge of all lower electron shells (total electron charge for shells of quantum number $n < n_\mathrm{valence}$). This means that electrons are different distances from the radius in atoms of different elements, a surprisingly important difference that plays a crucial role in biological system.

Unlike electrons, which are non-localized particles described by probability distributions, atoms have a volume and we can define an atomic radius in different ways. For some elements, we consider the atomic radius as half the bond distance by measuring the size of the molecules formed by particles. For other atoms, we define the atomic radius as half the lattice spacing between crystal structures of their ionic compounds.

As we move across a row in the periodic table, the effective nuclear charge increases, because the outer shell (valence) electrons do not effectively shield and there are more of them (so less shielding) as we go across a row, resulting in a higher effective nuclear charge. A higher effective nuclear charge results in a stronger attraction to the nucleus, so as we move right across a row, the atomic radius decreases.

Meanwhile, as we move across a column in the periodic table, the principle quantum number $n$ increases, so there are larger orbitals. Thus, as we move down across a column, the atomic radius increases.

Combining the two effects can be used to obtain the atomic radii of atoms of different elements relative to each other. For instance, iron and calcium are in the same row (so they have the same number of shells), but iron is to the right of the row, and thus pulls its electrons closer (that is, less effectively shields its outer electrons) so the iron atom has a smaller atomic radius as compared to the calcium atom.

Ionization energy

The ionization energy is the energy that is needed to remove the outermost electron from an atom or ion in gaseous state. The ionization decreases down groups (columns in the periodic table), and generally increases across the period, as electrons take more energy to remove for a larger effective nuclear charge (recall shielding) and when they are closer to the nucleus.

Paramagnetism, diamagnetism and ferromagnetism

A crucial quantum phenomenon that cannot be explained classically is spin. Spin is a fundamental property of almost all subatomic particles. To understand spin, first, we must remember that subatomic particles have two types of angular momentum: orbital angular momentum and spin angular momentum. The spin angular momentum is a form of angular momentum associated with subatomic particles that cannot be explained classically. Crucially, the spin angular momentum is quantized. Spin means that electrons possess tiny magnetic fields, and these tiny magnetic fields would line up against an applied magnetic field.

We observe that electrons can only take one of two spins - which we call "spin-up" and "spin-down". In addition, a pair of electrons must have opposite spins to share the same orbital. These quantum properties result in different material behavior when an external magnetic field is applied. To understand this, we first note that there are two different effects that result in magnetic interactions between an atom and an external applied magnetic field:

- The phenomenon of electromagnetic induction: an applied magnetic field interacting with electrons in an atom produces an induced magnetic field in the opposite direction, repelling the applied magnetic field and generating a repulsive force. This is known as Lenz's law, a key prediction of classical electromagnetic theory, and more can be read about it here.

- The phenomenon of spin magnetic moments: an applied magnetic field interacting with electrons in an atom causes the spins of the electrons to align with the magnetic field, resulting in an attractive force. This is a purely quantum phenomenon not predicted by classical theory.

For atoms that have valence orbitals in which every electron is paired, the opposite spins cancel each other out. Thus, spin magnetic moments have essentially no effect, so electromagnetic induction dominates and the net effect is repulsion, which we call diamagnetism ("d" for drive away). Meanwhile, for atoms that have valence orbitals in which there are unpaired electrons, there is a nonzero net spin and therefore the spin magnetic moment dominates, resulting in a net effect of attraction, which we call paramagnetism ("p" for positive attraction). Diamagnetic materials are the most common on the periodic table, followed by paramagnetic materials, but both are generally weak effects and disappear as soon as the applied magnetic field is removed. However, ferromagnetism is a special case of an attractive effect where the effect is very strong and does not disappear when the external magnetic field is removed - leading to what we call permanent magnets. From its root word ferrous - recall that the atomic symbol for iron is $\ce{Fe}$ - ferromagnetism only appears in a few elements, which, yes, includes iron, as well as nickel and cobalt (and in some alloys that contain these metals). We may summarize these results in the table below:

| Type of magnetic property | Effect | Strength | Found in... |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diamagnetism | Repulsive magnetic force | Weak | Most elements, including copper, gold, silver, and bismuth, and water |

| Paramagnetism | Attractive magnetic force | Weak | Some elements, including aluminium, oxygen, and titanium |

| Ferromagnetic | Attractive magnetic force | Strong, permanent | Very few elements - specifically iron, nickel, and cobalt |

From quantum to simpler models

While quantum mechanics is the basis of all chemistry and indeed all chemistry can be understood through quantum mechanics, quantum calculations are tedious and painstaking. Therefore, we typically resort to models that capture only some of the aspects of the full quantum theory. Several examples include the Lewis theory, Valence bond theory, and Valence shell electron pair repulsion (VSEPR) theory, which each explain the formation and structure of chemical compounds from different perspectives.

The Lewis model of chemical bonding

The Lewis model predicts how atoms of different elements form ions, molecules, and compounds by several key properties of valence electrons. The key ideas of Lewis theory follow from some simplifying assumptions based on the physical characteristics of atoms:

- Chemical bonds are formed by the transfer of electrons (in the case of ionic compounds) or sharing of electrons (in the case of covalent compounds) between different atoms.

- When forming bonds, the only electrons that participate are the valence electrons (also referred to as outer shell electrons), and all inner electrons can be effectively ignored.

- A stable configurations of atoms is achieved with a full valence shell, which determines which types of bonds are formed and how they are formed.

At the fundamental level, a chemical bond forms because it lowers the potential energy of a system of bonded atoms - and a stable configuration is that of the lowest potential energy. In the process of forming a bond, the decrease of potential energy of the atoms corresponds to a release of energy into the environment (in the form of light, heat, or sound) due to the conservation of energy.

Ionic bonding

We see recurring patterns of valence electrons throughout the periodic table. The alkali metals have one valence electron. The alkali earth metals have two valence electrons. The chalcogens (group 6, including oxygen and sulfur) have 6 valence electrons. The halogens (group 7) have 7 valence electrons. The noble gases all have eight electrons. Most transition elements have 2 valence electrons.

By examining these compounds, we observe that the noble gases are very stable and unreactive, but elements with atomic numbers adjacent to each noble gas are very reactive. This is because these adjacent elements need to gain or lose electrons to be able to have a stable configuration. Therefore, they form bonds readily by transferring or receiving electrons from another atom, with combustive (oxygen) or explosive (magnesium) effect. Therefore, we deduce that atoms transfer the number of electrons necessary to attain the valence-shell configuration of the closest noble gas. For instance, in losing one electron, sodium attains the valence-shell configuration of neon; similarly, in gaining one electron, chlorine attains the valence-shell configuration of argon, allowing them to both become stable.

In general, noble gases predominantly have 8 valence-shell electrons, so we often call this rule the octet rule. However, note that helium (the first noble gas) has 2 valence-shell electrons and thus it is the special case where the elements closest to helium (hydrogen and boron) can achieve the same valence shell as helium by just having 2 electrons in their valence shell.

This is the process of ionic bonding: Metals form cations (positively-charged ions) by losing enough electrons to get the same electron configuration as the previous noble gas, and non-metals form anions (negatively-charged ions) by gaining enough electrons to get the same electron configuration as the next noble gas. In our previous example, sodium and chlorine respectively gain and lose one electron to become the ions $\ce{Na^+}$ and $\ce{Cl^-}$.

Once bonded, the ions are arranged in a highly-ordered crystal lattice, held together by their electrostatic forces. The individual ions are all joined together with no starting or ending atom, so we do not speak of molecules of ionic compounds. We can only speak of formula units of ionic compounds, i.e. the same number of atoms as are within the chemical formula.

Lewis Theory predicts several important properties of ionic compounds. The strong and highly stable bonds mean that solid ionic compounds have high melting points and even higher boiling points, as a lot of energy must be put in to separate individual atoms from each other. The crystal lattice structure means that ionic compounds are hard, but also brittle because crystal layers can easily slide over each other even if they are individually very strong. When an ionic compound is dissolved, such as when salt is dissolved into water, the constituent ions are free to move and thus the ionic compound can conduct electricity.

Covalent bonding

While Lewis theory predicts many of the most important results of ionic bonding, its real power comes in its elegant explanation of covalent bonding and the resulting covalent compounds formed through covalent bonds.

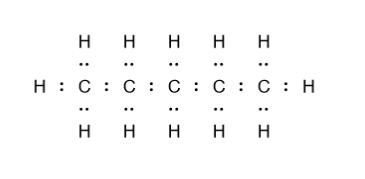

To demonstrate Lewis theory for covalent compounds, let us consider the classical example of water, $\ce{H2O}$. Water is formed by covalent bonds between a central oxygen atom and two hydrogen atoms. Recall that Lewis theory postulates that in the case of covalent compounds, electrons are shared, not transferred, between atoms to form bonds. A hydrogen atom has a single valence electron, while an oxygen atom has six valence electrons. We can show this by drawing Lewis structures, simplified representations of atomic valence orbitals, where dots indicate valence electrons:

When two hydrogen atoms each share their one electron with an oxygen atom, the result is a water molecule that allows all three atoms to have fully-filled valence shells, as is shown in the Lewis structure below:

In drawing Lewis structures, we follow these rules:

- The positions of the electrons around the atom doesn't matter, you can place them at the top, right, bottom, or left, or diagonally, that is a matter of personal preference as well as drawing convenience

- However, when electrons come in even pairs, they should be grouped together

- A pair of electrons form a bond between atoms, and can be represented with a straight line for readability (although using dots is also perfectly fine)

Thus, we may also draw the Lewis structure of water as follows:

Remember! A bond is formed by a pair of electrons, so a single bond is actually two electrons, a double bond four, a triple bond six, and so on. Similarly, we always speak of lone pairs of electrons - not single electrons!

Given this process of 1) identifying the number of valence electrons of atoms, 2) deducing how many electrons are necessary to form full valence shells (equivalent to the valence shell of the closest noble gas, and 3) drawing Lewis structures to join different atoms together with the bonds that produce these full valence shells, Lewis theory allows us to predict the chemical formulas of covalently-bonded and ionically-bonded compounds. This is how we know, for instance, that nitrogen gas is composed of two nitrogen atoms that are triple-bonded, as this allows both nitrogen atoms to gain a full valence shell:

The triple bond means that diatomic nitrogen (i.e. $\ce{N2}$) is extremely unreactive as breaking the triple bond requires a lot of energy. Conversely, nitrogen-based compounds can be highly reactive (e.g. nitroglycerin, a component of many explosives) as a nitrogen triple bond is formed by the reaction, releasing a lot of energy very quickly in the process - given that the constituent atoms in these nitrogen-based compounds readily break their (single or double) bonds to be able to form a far stabler nitrogen triple bond.

Bond polarity

The distinction between ionic and covalent bonding is sometimes not as distinct as it would first appear. Recall that when atoms bond, they may not be atoms of an equal number of valence electrons. For example, hydrogen chloride $\ce{HCl}$ is formed from a hydrogen atom that has one valence electron and chloride that has 7 valence electrons. This means that the hydrogen chloride molecule is negatively-charged on the chlorine atom end and positively-charged on the hydrogen atom end. We call such a bond a polar covalent bond and the molecule as a polar molecule with a dipole moment, a dipole moment being a charge difference across the molecule that produces a tiny electric field. At a certain point, the polarity is extensive to the point that we consider compounds no longer covalent compounds, instead considering them ionic compounds. Most compounds, however, fall somewhere between pure ionic and pure covalent.

We measure the polarity by electronegativity. Electronegativity is a measure of how strong an atom pulls in electrons towards itself. Higher electronegativity is generally associated with decreasing atomic radius and vice versa. The halogens have the highest electronegativities, receiving electrons to form ionic bonds. The alkali metals and alkali earth metals have the lowest electronegativities, as they pull on their electrons weakly and lose electrons easily to form ionic bonds. We exclude noble gases from measurements for electronegativity, in general. We also typically denote electronegativity by the symbol $\chi$.

Electronegativity is generally determined empirically; there are many published tables of electronegativities that can be looked up for reference. In a compound, the difference in the electronegativities of the individual atoms predicts the polarity. The following table explains:

| Type of bond | Difference in electronegativities ($\Delta \chi$) |

|---|---|

| Pure covalent | $\Delta \chi < 0.4$ |

| Polar covalent | $0.4 \leq \Delta\chi < 1.9$ |

| Pure polar | $\Delta \chi > 1.9$ |

Resonance

In many cases, the geometry of a given molecule means that multiple Lewis structures are possible. The true molecule actually occurs in all the different predicted Lewis structures in different proportions, which we refer to as resonance. This is also called a delocalized bond, and we call the structure a resonance structure. Consider, for instance, the carbon dioxide molecule, which has three resonance structures:

Resonant structures must have the same bonds. The only difference between the respective Lewis structures is that the bonds are placed in different locations. We draw a resonance structure by placing several Lewis structures adjacent to each other and draw a double sided arrow $\leftrightarrow$ to show that multiple structures are possible. Of these Lewis structures, we choose the preferred Lewis structure. There are several criteria used to determine the "best" Lewis structure, and we will discuss each of these below.

Formal charge

Recall that the reason covalent bonds form at all is to lower potential energy of atoms, which means minimizing the electrostatic repulsion between electrons. The reason for this is that all electrons have a negative charge, and charges of the same sign repel, which increases potential energy. Therefore, the configuration of electrons within a covalently-bonded compound will seek to lower the potential energy as much as possible by decreasing the effective charge, which decreases the electrostatic repulsion. We may quantify the effective charge of a compound with a "book-keeping" number called the formal charge, which we can calculate by taking the number of valence electrons of each atom (in its elemental state), and then subtracing both the number of nonbonding electrons and half the number of bonding electrons. Mathematically, we can formulate it as follows:

$$ Q_F = \sum \limits_\mathrm{atoms} \left(\text{valence\ }e^- - \text{nonbonding\ }e^- - \dfrac{1}{2} \text{bonding\ }e^-\right) $$

In the case where multiple Lewis structures are possible, the best Lewis structure is typically the one that minimizes formal charge, and thus, this is also the most common Lewis structure that is observed experimentally.

Covalent bond strengths

Triple bonds are strongest, followed by double bonds, followed last by single bonds (which are weakest). We may quantify this with a metric known as the bond order.

Bond order = Total number of bonds (for a double bond we count it as two bonds, for a triple bond we count it as three bonds, etc.) divided by number of bond groups (a group can be a single bond, a double bond, or a triple bond; all of these are considered a single bond group). For example, $\ce{N2}$ has one bond group (since it has just one $\mathrm{N}\equiv\mathrm{N}$ bond, which we consider a single group) but has three bonds (since its nitrogen-nitrogen bond is a triple bond). So its bond order is $3 / 1 = 3$. In general, the higher the bond order, the more stable the molecule.

Exceptions to the octet rule

Odd-electron species, that is, molecules in which the sum of all the valence electrons (of each atom) is an odd number, have an incomplete octet on the central atom(s). For instance, nitrogen dioxide ($\ce{NO2}$) is an odd-electron species. In this case, as nitrogen is the central atom in $\ce{NO2}$, it simply does not have enough valence electrons to form a full octet. Thus, it forms the most stable configuration it can - which results in $\ce{O-N=O}$, a single bond to one oxygen atom and a double bond to the other oxygen atom.

For third-row elements and beyond, we also have expanded octets, where an element can hold more than an octet in its outer shell. This gives them more bonding electrons, allowing for more and stabler bonds (for instance, double instead of single bonds) and also lowering their formal charge (as bonded electrons count half as much as lone pair electrons when calculating formal charge).

VSEPR theory and bond geometries

We have already seen that Lewis structures can predict many properties of molecules, especially after the inclusion of formal charges. However, Lewis structures do not tell us much about the true geometries of molecules. For this, we turn to valence shell electron-pair repulsion (VSEPR) theory.

The central idea behind VSEPR is that the electrostatic repulsion between electrons causes electrons to arrange themselves to minimize the repulsion between the electrons. This leads to molecules with different but predictable shapes.

Note: In VSEPR the lone pairs of non-central atoms has no effect - we consider a central atom as an atom that has at least two bonds attached to it and (typically) resides in the center of a molecule and has the most bonds attached. So in VSEPR we usually analyze molecules that are composed of at least three atoms. Lewis theory is sufficient for two-atom molecules.

Electron geometry

We first consider idealized geometries in the VSEPR theory. Both bonding pairs and lone pairs constitute electron groups. Each bond (whether single, double, or triple bond) counts as one electron group, and each lone pair also counts as one group. E.g. for $\ce{PCl3}$ which has a single lone pair and three bonding pairs, there are four total electron groups. By writing down the number of bond groups we can find the electron geometry - that is, the 3D arrangement of the electrons across the molecule - by the table below:

| Number of electron groups | Electron geometry | Bond angle | Visual appearance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Linear geometry | 180 degrees |  |

| 3 | Trigonal planar geometry | 120 degrees |  |

| 4 | Tetrahedral geometry | 109.5 degrees |  |

| 5 | Trigonal bipyramidal geometry | 120 degrees between equatorial (middle) atoms, 90 degrees for axial (top/bottom) atoms |  |

| 6 | Octahedral geometry | 90 degrees (all bonds perpendicular) |  |

Bond diagrams licensing information

For instance, take note of the following examples of electron geometry:

| Compound | Lone pairs | Bonding pairs | Total pairs | Electron geometry | Idealized bond angle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $\ce{CO2}$ | 0 | 2 | 2 | Linear | 180 degrees |

| $\ce{H2O}$ | 2 | 2 | 4 | Tetrahedral | 109.5 degrees |

| $\ce{SO2}$ | 1 | 2 | 3 | Trigonal planar | 120 degrees |

| $\ce{PCl5}$ | 0 | 5 | 5 | Trigonal bipyramidal | 120 degrees for middle bonds, 90 degrees for upper and lower (perpendicular) bonds |

| $\ce{SCl6}$ | 0 | 6 | 6 | Octahedral | 90 degrees, all bonds perpendicular |